Nuclear War Evaded:

Remembering the Cuban Missile Crisis

Written by Justin Lamb

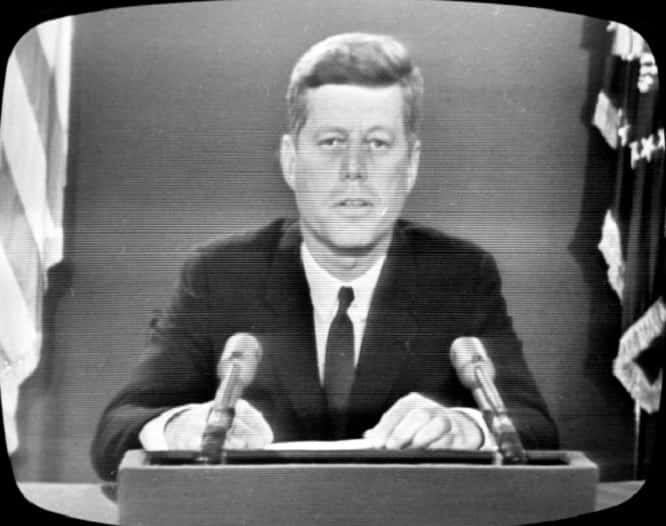

President Kennedy informs the nation of the presence of missiles in Cuba.

(JFK Presidential Library, Public Domain)

In October 1962, the world stood on the brink of nuclear war when tensions in the Cold War became heated between the United States and Soviet Union. Fears began when United States intelligence learned of the installation of nuclear-armed Soviet missiles on the island of Cuba just 90 miles from the coast of Florida. When President John Kennedy was notified of the missiles on October 16, he began secret meetings with his national security advisors and military leaders to devise which course of action to take. The group of leaders became known as ExCom and news of the missile installation in Cuba was kept from the American people in order to prevent a public panic.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff unanimously agreed that a full scale attack of Cuba was the only option and urged President Kennedy to invade the island nation that had aligned itself with the communist Soviet Union in 1960. President Kennedy was skeptical though. He knew that the installation of nuclear missiles so close to the American coastline gave the Soviets the upper hand in the Cold War and the power to quickly reach targets anywhere in America. But he also understood that a “trigger happy” response could very well launch the nation into a nuclear war thus staring World War III.

The United States military was put on high alert as units were moved to bases in the southeastern U.S. and were prepared to invade Cuba at a moment’s notice. On October 18, President Kennedy met with Andre Gromyko, Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs at the White House. Not knowing that President Kennedy knew of the missile build up in Cuba, Gromyko insisted that the Soviet Union’s alliance with Cuba was only a defensive measure and posed no threat to the United States. Kennedy, without revealing his knowledge of the existence of the missiles, read to Gromyko the public warning he gave in a September 4 speech that the “gravest consequences” would follow if significant Soviet offensive weapons were introduced into Cuba.

As ExCom continued to debate what measure of action to take, President Kennedy kept up his public appearance in order not to create a public alarm. While on a campaign trip in the Midwest on October 20, President Kennedy cancelled his events and suddenly returned to Washington to meet with ExCom to draft a final plan of action. “To avoid public suspicion, Kennedy and his doctors fabricated a cold diagnosis for president allowing him to return to the nation’s capital without creating a panic.”

After a meeting with General Walter Sweeney of the Tactical Air Command who told the president that an air assault could not guarantee destruction of the missiles, President Kennedy concluded that a naval blockade would be the first course of action followed by an invasion if the blockade did not succeed.

The time had come to inform the American people of the grave situation. On the morning of October 22 as a speech was prepared for a national address to the public, President Kennedy telephoned former presidents Truman, Hoover, and Eisenhower of the situation followed by a briefing of his cabinet and Congressional leaders. Before going on national television, President Kennedy wrote a letter to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev “I have not assumed that you or any other sane man would in this nuclear age, deliberately plunge the world into war which is crystal clear no country could win and which could only result in catastrophic consequences to the whole world, including the aggressor.”

At 7pm, President Kennedy notified the nation and the world about the existence of the missiles in Cuba. He went on to explain his decision to enact a naval blockade, or quarantine as he referred to it, of the small communist island which relied heavily on Soviet aid and made it clear that the U.S. was prepared to use military force if necessary.

“The path we have chosen for the present is full of hazards, as all paths are; but it is the one most consistent with our character and courage as a nation and our commitments around the world. The cost of freedom is always high, but Americans have always paid it. And one path we shall never choose, and that is the path of surrender or submission. Our goal is not the victory of might, but the vindication of right; not peace at the expense of freedom, but both peace and freedom, here in this hemisphere, and, we hope, around the world. God willing, that goal will be achieved.”

The Soviet Union responded by telling the United States that the blockade would be ignored, and on October 23, the United States raised the readiness of strategic air command forces to DEFCON 2 and American B-52 bombers went on continuous airborne alert. Leaders were bracing for the worst.

The days following President Kennedy’s address, people around the world anxiously waited for response from the Soviet Union. Some Americans hoarded food and gas in fear of an impending nuclear war. Jeri Lovett-Harrell of Benton was only a teenager at the time, but remembered how people in Marshall County prepared. “I remember people building bomb shelters, and in fact, there was one on Green Hill Drive,” Lovett-Harrell recalled. “I also remember that we students were told we would go from the school in Benton to the courthouse in case of nuclear attack.”

On October 24, a Soviet ship bound for Cuba neared the naval blockade as the world nervously awaited to see what would unfold. If the Soviets would have breached the blockade a military confrontation would have escalated with possible nuclear strikes. However, Soviet ships stopped just short of the blockade and gave the first sign of averting war between the two nuclear nations. Benton resident Martha Lewis remembered this tense time in American history, “I remember following it all on TV and being concerned,” Lewis recalled. “We were anxiously watching very closely to see if the Russian ships would turn back from the naval quarantine, and everyone breathed a sigh of relief when this happened.”

Although the blockade had not been breached, the standoff between the two nations continued as the missiles were still in place in Cuba. The United States requested an emergency meeting of the United Nations Security Council on October 25 where U.S. ambassador Adlai Stevenson confronted Soviet ambassador Valerian Zorin about the existence of the Cuban missiles. When Zorin refused to answer Stevenson’s question about the missiles, Stevenson declared, “I am prepared to wait until Hell freezes over for my answer.”

Two days later on Saturday. October 27, the crisis reached its peak when an American recon plane was shot down over Cuba claiming the life of the 35-year old pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson. The United States invasion force was put on high alert on the coast of Florida as the United States teetered on the brink of war. “I thought it was the last Saturday that I would ever see,” recalled Defense Secretary of Robert McNamara who believed nuclear war was imminent.

Cooler heads prevailed and diplomacy won the day as President Kennedy and Soviet Premier Khrushchev, who had corresponded and negotiated throughout the crisis, came to an agreement in which the missiles in Cuba would be removed with the promise that the United States not invade Cuba. In an additional secret agreement, President Kennedy agreed to remove U.S. obsolete Jupiter missiles from Turkey. By October 28, 1962 the world’s brush with nuclear war began to ease as Khrushchev announced on Russian radio of the dismantling of the Cuban missiles. With the missiles gone, the naval blockade of Cuba ended on November 20, 1962. The world breathed a sigh of relief.