Looking Back:

Dr. H.W. Ford

Written by Justin D. Lamb

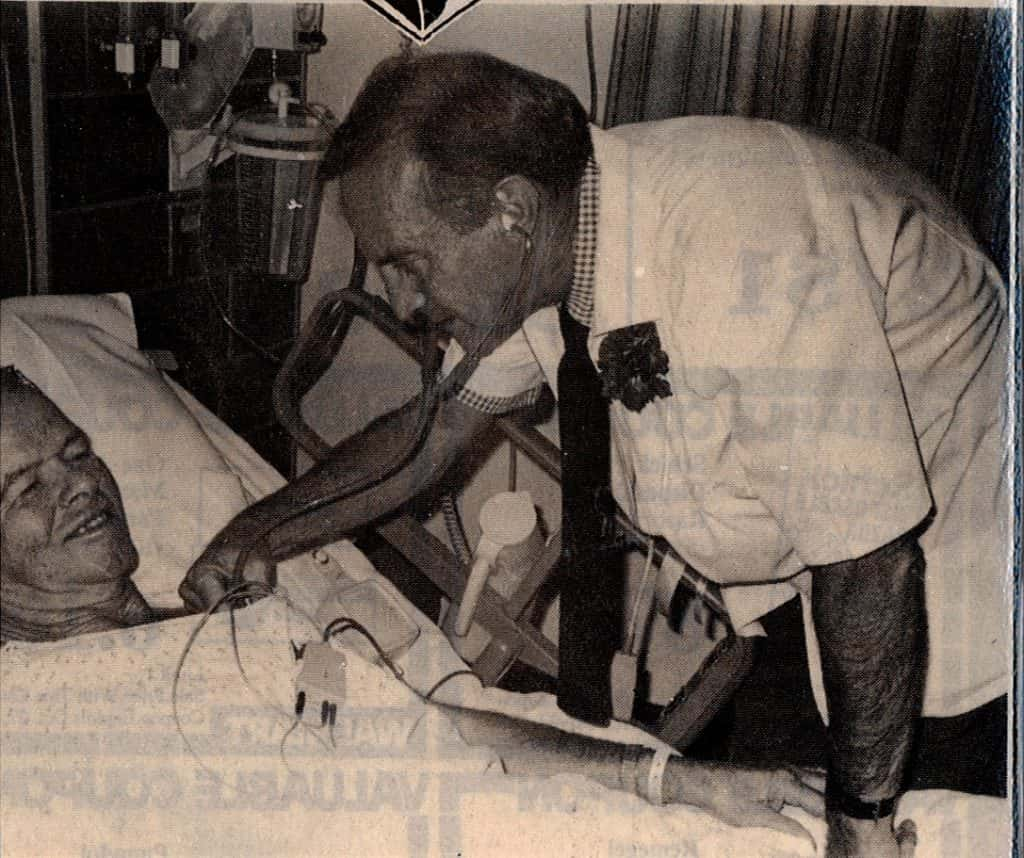

Dr. Ford checks in on a patient at Marshall County Hospital in the 1970s.

(Courtesy of H.W. Ford)

Most doctors are known for their bad handwriting. But the reason for Dr. H.W. Ford’s poor handwriting skills may be different than other doctors. “The only handwriting lesson I ever got was from a 2nd grade classmate of mine named Bluegill,” Ford recalled.

“My parents started me to school too early. I was only 5 years old in first grade and I didn’t take much of a liking to it,” Ford commented. “My teacher, Miss Katie Hill, had a hard time straightening me out. I would get up and leave class without being excused and I played hooky a lot. I just didn’t take an interest. “

Ford’s likening to school wasn’t much better when 2nd grade rolled around either. “During second grade, I started out doing the same thing, playing hooky and cutting out early. Well, one day when I was playing hooky, they started learning cursive writing and I came back the next day and everybody in the class was writing except me. So, I took my paper and pencil up to the teacher’s desk and asked her to show me how to write. She gave me a chewing out telling me that I never try and she wasn’t going to waste her time with me. So I went back to my seat and my table mate was a boy we called ‘Bluegill.’ I said ‘Bluegill what am I going to do? I don’t know how to write and the teacher said she wasn’t going to help me.’ Bluegill turned to me and said, “Aw, hell, just print the letters and put tails on those sonsofbitches an’ run ‘em together and that’s all you gotta do.’ And to this day, that is the only writing lesson I have ever had!”

A young HW Ford in Calvert City.

(Courtesy of HW Ford)

H.W. Ford was born to Homer Ford and Larrie Kennedy Ford on Sunday, November 8, 1931 in Calvert City. “When I was born my parents gave me the initials “HW” and I don’t have a name. The ‘H’ came from my dad and the ‘W’ was my grandfather’s middle name,” Ford said. “They gave me initials and no name.”

When H.W. was two and half years old, his parents opened up a grocery store in Calvert City where the young boy worked until he was sent to help his grandfather in the fields at ten years old. “My granddad decided he needed help and there wasn’t any use of me just loafing around that store, so they sent me to work with him,” Ford recalled. “I never forget the first day. I was only ten years old and I had never driven a horse or a mule. He hooked up me and a rastus plow up to an old mule and took me to one of his old corn patches. He said ‘H.W. you plow this corn and don’t you stop that mule for anything.’ My granddad showed me what to do and then he went into another field out of sight,” Ford remembered. “

Ford’s first time in the field went well until the old mule started giving him trouble. “After I made one round by myself, the mule decided he had to pee. I didn’t know what was happening. He was shaking and moving and pulling and I just thought the mule was trying to lay down on me, so I laid the whip to him and got him going again. We made another round and the mule stopped again and done the same thing, so I laid the whip to him again. We finally done that about three times and that mule turned around and looked at me with those big brown eyes with a look like he was saying ‘What the hell is going on?’ That went on all afternoon and finally the mule just started peeing as we plowed the rows. By the end of the day, I was worn out and the mule was worn out, but I wasn’t going to stop for anything because my granddad had told me not to. Finally my granddad came back and asked how it went and I told him, “Pa, it was all I could do to keep that mule from stopping to pee.’ He said, ‘Well, you could have let him to stop for that!’”

When Ford was growing up in Calvert City as a child in the ‘30s and ‘40s it was a much different place than it is today. “Calvert was a rough place back in my younger days,” Ford recalled. “It was an old river town and the river workers would congregate in town on Saturdays and there would be fights and brawls all the time. It got so bad there would be blood in the streets.” Things in Calvert City began to turn around during World War II. “The war ended the Depression and with the Kentucky Dam good things started to happen in Calvert,” Ford stated. The construction of the Kentucky Dam brought electricity to Marshall County and led to the construction of the chemical plants in Calvert City.

Ford remembered the 1937 flood and the destruction it brought to parts of Marshall County. “I remember when my Dad and I went down to the railroad crossing at Calvert City and there was Coast Guard folks pulled in there in boats. The water was so high it was over the houses. I remember one afternoon we walked down the railroad tracks to old Gilbertsville and I remember seeing a turnip float up from the flood water. We peeled that turnip and ate it and to this day, I don’t eat a turnip that I don’t think about eating that turnip that floated up that day.”

After graduating from Calvert City High School in 1949 and following a short stint in college, Ford served in the United States Air Force during the Korean War. “The war broke out when I was in college at Murray,” Ford said. “I wasn’t doing too good in college at the time and the university said if I enlisted they would give me my grades so I joined.” Ford served overseas at Okinawa where he was a radio mechanic.

After the war, Ford went back to Murray State and completed his degree. “The military was the best thing for me. I matured and grew up,” Ford stated. “I was much more focused on getting an education after my military service,” Ford said. During his college years, Ford met Miss Beverly Brawner of Calloway County and the two married on June 7, 1958 in New Concord. “I got to know her during my junior year and we started dating the following year,” Ford recalled.

At the instance of his mother, Ford decided to become a doctor and enrolled in medical school at the University of Louisville. “All my life, my mother wanted me to become a doctor,” Ford recalled. “When I came back to Murray after the military, I couldn’t think of anything else I wanted to do, so I decided to go in that direction.” Ford graduated from medical school in 1962.

“I went to St. Louis after medical school and interned over there for two years,” Ford said. Dr. Ford returned home to Marshall County in 1964 where he opened up practice. “I had got to know Dr. Ken Ellis in medical school and we had decided if we got out at the same time we would go into practice together,” Ford recalled. “He got drafted into the military in 1962 and was discharged in 1964. I practiced with Dr. Harold King until Dr. Ellis came back in 1964 and we opened practice,” Ford recalled.

“In those days we did it all,” Ford recalled. “We made house calls, delivered babies, helped in surgery. We had to cover the emergency room and were on call all the time at the new hospital because there wasn’t anybody hired to be there.”

“The hospital in Benton first opened the year I came back after medical school,” Ford recalled. “It was supposed to open in July 1964 which was the date I was to arrive back in town, but it had to be opened a few months early to assist the victims of the 1964 tornado,” Ford said. “So I came to work there a few months after it opened.” Dr. Ford went on to become Chief of Staff at Benton Municipal Hospital [later Marshall County Hospital] on several occasions.

A lifelong Republican, Ford tried his hand at political office in 1973 when he ran for county coroner. “The folks at Filbeck-Cann Funeral home asked me to run,” Ford recalled. “Jess Collier [of Collier Funeral Home] was coroner then and the two funeral homes were big rivals. Jess and I were friends and neither one of us hardly campaigned at all and eventually Jess won the race,” Ford remembered about his one and only race for public office.

Dr. Ford’s biggest impact on the community is his work with the Marshall County Health Department. “I’ve been associated with the health department so long, I don’t remember how long,” Dr. Ford joked. Dr. Ford was appointed to the Marshall County Public Health Board in the 1960s by County Judge John Rayburn and still serves today. Dr. Ford was medical director at the health department from 1990 until his retirement in 2012.

“Public health has changed dramatically over the years,” Ford said. “When I was a kid, all the health department did was give immunizations to children. The doctor and nurse would show up to the school in Calvert City and we would all about faint because we knew we were going to get shots.”

Ford said the greatest achievement in public health can be traced back to immunizing children. “The best example of success is polio. It was a terrible, debilitating disease,” Ford said. “Thanks to the Saulk vaccine, we’ve wiped out polio. We vaccinate for measles, mumps, whooping cough and don’t see those diseases like we used to.” When he first started practicing in Benton, Ford said the community was in the grips of a measles epidemic. He credited vaccination programs for eliminating similar epidemics and the death of children to pediatric diseases.

Dr. Ford has been an avid competition runner for years. “When Beverly was teaching at the high school, the track coaches got to her running at the school and she got me started,” Ford recalled. “Next thing I know I am running 5k races then 10k then half marathons. Then I finally ran 10 marathons. I ran Boston, Chicago, St. Louis, New York, among others.”

Often described as a quiet, patient man and a knowledgeable doctor, Dr. H.W. Ford has left a lasting impact in healthcare in Marshall County. For his numerous contributions, the Marshall County Chamber of Commerce awarded Dr. H.W. Ford with its citizen of the year award in 2013. Additionally, the board room at the new Marshall County Health Department was dedicated in honor of his many years of service.