Kentucky’s Connection to George Wallace

Written by Justin D. Lamb

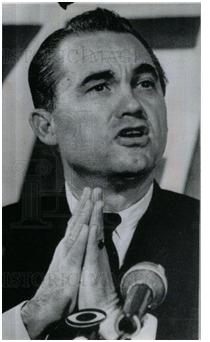

Press photo of Governor George C. Wallace speaking at Southern Governors Conference hosted at Kentucky Dam Village in September 1966.

(Collection of the author)

American politics has never had a more controversial and more colorful character as Alabama Governor George C. Wallace. Known for his fiery oratory that ignited his audiences, Governor Wallace first gained national recognition in June 1963 when he infamously carried out his promise to stand in the “schoolhouse door” to prevent the enrollment of two black students Vivian Malone and James Hood at the University of Alabama. Following the nationalization of the Alabama National Guard by President Kennedy, the two students were allowed to enroll, but the stunt catapulted Wallace to national fame.

Interestingly, though, Wallace wasn’t always a hardliner on segregation, and in fact, began his political career as a moderate on the politics of race. During his first run for the governor’s office in 1957, he had the full support of the NAACP and spoke out against the Ku Klux Klan, but this moderate strategy caused him to be defeated by nearly 35,000 votes in Jim Crow Alabama. The defeat deemed the ambitious politician to never be outmaneuvered again.

Almost overnight, Wallace, the ultimate political opportunist, made a Faustian bargain in order to politically survive and changed his position on segregation to line up with the beliefs of the majority of Alabama’s electorate at the time. “You know, I tried to talk about good roads and good schools and all these things that have been part of my career, and nobody listened,” Wallace later reflected. “And then I began talking about race, and they stomped the floor.” It was this fiery populist rhetoric that allowed Wallace to become Governor in 1962.

Riding a wave of national attention following the schoolhouse door incident in June 1963, Wallace began flirting with the idea of running for President of the United States with a platform that was in direct opposition to President Lyndon Johnson’s passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Wallace called the act “a fraud, sham, and a hoax which allowed the federal government to overstep its constitutional bounds.” Wallace soon realized that he didn’t have enough delegates to mount a formidable challenge for the Democratic nomination against the popular President Johnson at the 1964 Democratic Convention, so he abandoned his hopes for the presidency in 1964.

Wallace’s aspirations for higher offices didn’t wane, however. Throughout the remainder of his term as Alabama Governor, Wallace continued to be a national voice against the Civil Rights movement and a strong defender of states’ rights. In late 1965, he proposed a constitutional amendment to give states and state courts the sole jurisdiction over their public schools thus preventing a federal law to integrate them.

Kentucky, however, led by Democratic Governor Edward “Ned” Breathitt was moving in a different direction. On January 27, 1966, the Kentucky General Assembly thanks in a large part to Governor Breathitt and House Speaker Shelby McCallum of Benton, passed the first Civil Rights act in a southern state. The bill passed with little opposition and opened all public accommodations to people of every race and prohibiting racial discrimination in employment by firms that employed eight or more people. The act applied to many kinds of businesses not covered by the federal statute, and approximately ninety percent of the businesses in Kentucky were affected, compared to only sixty percent that were covered by the federal statute.

Additionally, as Chairman of the Southern Governors Association, Breathitt came out against George Wallace’s proposed constitutional amendment to give states and state courts sole jurisdiction over their public schools, preventing a federal law to integrate them. Breathitt’s opposition helped prevent the Southern Governor Association’s endorsement of the amendment, since endorsement required a unanimous vote.

In September of 1966, Kentucky Dam Village in Gilbertsville was host to the 1966 Southern Governors Association Conference. Sixteen governors from all across the South were in attendance including Governor Breathitt and Governor Wallace. The two men, both Democrats, were polar opposites on Civil Rights, but had a good working relationship on other issues. At the conference, Civil Rights issue took a backseat, as economic development, was the prime topic. However, George Wallace, teased the audience with a preview of things to come when he opened the door to a possible presidential run in 1968.

As the weeks and months went on following the 1966 Southern Governor’s Conference, Wallace soon began toning down his segregation stances and adopted issues important to blue collar working whites who felt alienated by both the Democratic and Republican parties. “There ain’t a dime’s worth of difference between the Democratic and Republican parties,” Wallace proclaimed. Wallace soon saw an opportunity and mounted a campaign for the Presidency in 1968 on his newly formed third party ticket, the American Independent Party.

The year 1968 was a chaotic year in American history with race riots in several major cities, college protests all across the country against the Vietnam War, assassinations of major political figures, and a seemingly overall break down of law and order. Many felt that America was falling apart.

George Wallace echoed many people’s concerns and was the first candidate to call for the restoration of “law and order.” He began to gain support outside of the south with his plain speaking rhetoric which resonated with a silent majority of Americans who were growing tired of the civil unrest at home. Following an incident in California where a protestor laid down in front of President Lyndon Johnson’s car, Wallace pledged a few days later at a campaign rally that “if some anarchist lies down in front of my automobile, it will be the last automobile he will ever lie down in front of.” It was rhetoric such as this that broadened Wallace’s appeal outside of the South.

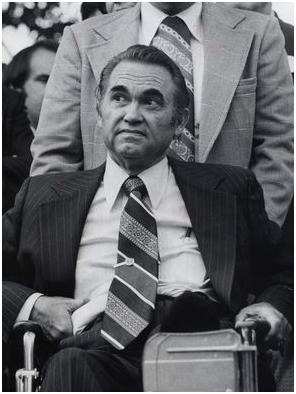

George Wallace visits Fancy Farm Picnic in 1975.

Knowing full well that he could not gain enough electoral votes to win the presidency, Wallace’s campaign strategy was to pull enough electoral votes from Republican Richard Nixon and Democrat Hubert Humphrey and to force the House of Representatives to decide the election. As the power broker, Wallace hoped that southern states could use their clout to end federal efforts at desegregation.

When time came to choose a running mate, Wallace’s first choice was former Kentucky Governor and Senator A.B. “Happy” Chandler, who told his advisors that he would accept when formally asked. However, when some of Wallace’s more radical supporters found out, they objected because of Chandler’s efforts to desegregate professional baseball during his time as baseball commissioner by supporting the hiring of Jackie Robinson. The offer was rescinded and went to General Curtis LeMay instead.

Richard Nixon ultimately took the Presidency in 1968, but Wallace carried 5 states and gained 46 Electoral votes. In Kentucky, Wallace received 18 percent of the vote and carried six counties by a large margin including Fulton and Hickman in the Jackson Purchase. Thanks to the efforts of former Benton City Police Chief, Charles “Chewing Gum Charlie” Carroll, who was a strong Wallace booster, George Wallace received over 2,500 votes in Marshall County. House Speaker Shelby McCallum, though, kept Marshall County in the Democratic column, but Governor Breathitt couldn’t do the same for his home of Christian County which went in the Wallace column. Overall, Kentucky’s electoral votes went to Republican Richard Nixon.

Wallace mounted another presidential run in 1972 on the Democratic ticket and many felt he would gain the nomination. However, in May 1972, he was shot at a campaign rally which left him paralyzed and confined to a wheelchair the rest of his life. However, his appeal in western Kentucky lived on through they years and he visited the Fancy Farm Picnic in 1975. While speaking at the famed political event, a flashbulb from a photographer’s camera popped and Wallace flinched. “I hope you get that fixed,” Wallace told the photographer, “Because I’m still a little gun-shy.”