The Trial of Lucy Griffith

Written by Justin D. Lamb

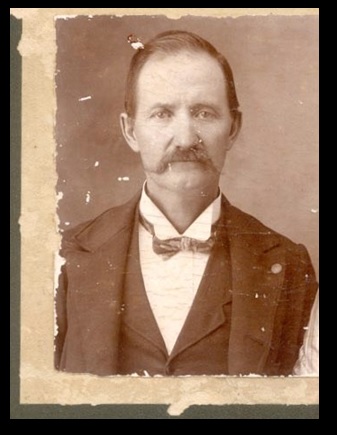

Edward and Lucy Griffith

Photographed just months before the murder

Courtesy of West Kentucky Genealogy

“My God, if you let him live, I will never do wrong again,” screamed Lucy Griffith as she cried hysterically in the arms of her brother-in-law Edgar Starks on the morning of April 29, 1911. Spectators from all across Benton began to gather at the Griffith home as Dr. Van A. Stilley and County Coroner Dr. Benjamin T. Hall removed the body of one of Marshall County’s most respected businessmen. Just one hour prior, Edward Griffith had fallen ill and died an agonizing death on the floor of his own kitchen as a result of strychnine poisoning.

As he learned of his son’s death, Winfield Griffith left his post at the Griffith’s Dry Goods store on Main Street and made a dash to his son’s home. As soon as he arrived, he went after Lucy and accused her of killing his son. Lucy, who was an emotional wreck, strongly denied the charges and claimed Edward had fallen ill after he had taken a drink of brandy which his father had given to him just a few days prior. The bottle of brandy was confiscated by Sheriff L.E. Wallace who sent it with Dr. Hall which later tested positive for strychnine.

Sheriff Wallace turned the results over to County Attorney Elbert Cooper and people from all across the county packed the court yard of the Marshall County Courthouse in early May as Judge Price reviewed the evidence being presented. By midafternoon, Judge Price issued a warrant for the arrest of Lucy Griffith for the murder of her husband. With the warrant in his hand, Sheriff Wallace took the short walk from the courthouse to the Griffith home and placed Mrs. Griffith under arrest. A shaken Lucy Griffith was brought before Judge Price who set her bond for $4,000 which she immediately paid.

Griffith home on Main Street in Benton

Site of the Murder of Edward Griffith

Jesse Edgar Starks (far left), Edward Griffith (second from the left), and Lucy Griffith (fourth from the left)

Everyone in the community was shocked at the news of Lucy Griffith’s arrest. The Griffith family was one of the most prominent and well respected families in the county and many could not believe what they were hearing. Edward Griffith was a successful businessman in Benton and owned one of the most profitable dry goods stores in area. ( Note: The store was located at 1106 Main Street and now houses Old Crow Studios). His father, Winfield Griffith, was a Union Army hero, Benton Postmaster, and leader of the local Republican Party with connections as far up as United States Senator William O. Bradley.

Lucy also came from good stock. Her father, James T. Ozment, was former Marshall County Jailer and one of the largest landowners in Benton. With the prominence of those involved, the town of Benton was quickly divided into two factions—— those who thought Lucy was innocent and others who believed thought she was a cold blooded murderer.

After Lucy’s release on bond, the Sunday school class which she taught at the Benton Methodist Church gave her a vote of confidence and pledged to support her. The Baptist Church in Benton in which Winfield Griffith was a deacon pledged to do everything in their power to make sure Lucy was prosecuted. When the Grand Jury convened in early July, Commonwealth Attorney John G. Lovett and County Attorney Elbert Cooper presented the evidence and asked for an indictment against Lucy Griffith for the murder of her husband. After a week of hearings at the Marshall County Courthouse, the Grand Jury voted not to indict Lucy Griffith.

A few days after the ruling, members of the Grand Jury received a letter from a band of night riders warning them to leave the county for failure in producing an indictment. The note read: “You are warned to leave the county at once or suffer violence. Because you voted against indicting Mrs. Lucy Griffith for poisoning her husband. That is the reason we do not want you as citizens. This organization is 500 strong. Signed—Ominous N.R.” Lucy Griffith also received a letter on her doorstep warning that she would be killed. The notes were turned over to the sheriff’s office and when the December term of the Circuit Court convened, the Grand Jury was once again called to hear the same evidence against Lucy Griffith. In a short amount of time, the Grand Jury voted to indict her for the murder.

As 1911 turned into 1912, Western Kentucky was intrigued with the dramatic case. Lucy Griffith had become the first woman in Marshall County’s history to be indicted with willful murder and many found it hard to believe that such a prominent lady could do such a dreadful act.

Lucy Griffith certainly was not a woman of her time. In an era when women were to be seen and not heard, Lucy was outspoken which irked her traditional father-in-law. Winfield Griffith and Lucy Griffith’s relationship had been strained ever since she married his son in 1901. Edward Griffith was a known drunkard and Lucy, who was a devout Methodist, was strongly against drinking. She threatened several times to leave Edward because of his alcoholism, womanizing, and the physical abuse. However, the very religious Winfield Griffith stopped the couple from ending their marriage on several occasions, most recently in 1910. With the unhappiness of her marriage, Lucy was driven into the arms of her brother-in-law, Jesse Edgar Starks. At a community church picnic a few weeks prior to the death of Edward Griffith, R.G. Treas caught Lucy and Edgar Starks kissing by a well. Edward Griffith soon learned of his wife’s infidelity which placed a greater strain on the marriage.

In March 1912, Circuit Judge William Reed arrived from Paducah and made his way upstairs to the crowded courtroom to preside over what was becoming one of the most thrilling murder trials in Marshall County’s history. The first witnesses called for the Commonwealth were the three doctors who attended to Edward Griffith on the day he died and they all testified that Edward had shown every symptom of strychnine poisoning. Dr. Stilley added in his testimony that Edward Griffith was noticeably upset with his wife and when she tried to comfort him that he told her to get away and accused her of killing him. Dr. Stilley added that Edward had whispered in his ear and told him that Lucy had poisoned him.

Edward Griffith’s father, Winfield S. Griffith, was called to the witness stand and testified that the marital relations between his son and Lucy had been strained for quite some time due to Lucy’s infidelity. He also added that just a few months prior Lucy had withdrawn five hundred dollars of her money out of the Griffith bank account and had planned on running off with Starks. Griffith also recounted his son’s last words to him, “Pa, they poisoned me. Pa, I never told you a story in my life. If I die, they poisoned me.”

Winfield S. Griffith

Benton Postmaster and father of Edward Griffith

Several witnesses were called for the defense who testified that Edward Griffith was a habitual drunkard and a womanizer. Lucy Griffith testified in her own behalf and stated that on the morning her husband died that he had went to work early and came back home around 7:30 am. She added that when Edward arrived home to eat breakfast that he had already been drinking and tried to force himself on her. Lucy stated that she pushed him away and Edward became frustrated and ended his pursuit. Lucy also testified that after Edward took a drink of the brandy that he began to have a seizure on the floor of the kitchen and that she had done everything in her power to help him. Lucy stated that she was devoted to her husband and they had begun to work things out. In the closing arguments, the defense attorney, W.A. Barry argued that it could not be proven who put the poison in the brandy and that Dr. Stilley and Winfield Griffith’s accusations could not be proven. On April 6, the fate of Lucy Griffith was given to the jury and after a four day deliberation, the jury was deadlocked. After two days of wrangling, Judge William Reed declared a mistrial.

A new trial was set for December 1912. During his second testimony, Winfield Griffith claimed that he believed that the poison may have not been intended for his son, but for him. He went on to say that Lucy may have been trying to kill him so that she could divorce Edward and run away with Starks. The defense introduced their star witness, Miss Ottie Starks, who was a cousin of Edgar Starks and a clerk at Starks Drug Store in Benton She testified that Edgar Starks had come to the drug store the day before Edward Griffith’s death to use the drug measuring scales. She stated that Starks was in the back using the scales for approximately ten minutes and that she saw him put something in his pocket, but she could not verify what it was. She also confirmed that Starks Drug Store did sell strychnine and that is was very easy for Starks to obtain.

In their closing arguments, the defense argued that all the evidence against Lucy Griffith was circumstantial and that nothing could be proven. At four o’clock on Thursday, December 12, 1912, the fate of Lucy Griffith was placed in the hands of the jury. Several people crammed into the courthouse while others waited for word outside. After a few hours deliberation, Lucy Griffith was found not guilty for the murder of Edward Griffith. When the verdict was read, a newspaper reporter for the Mayfield Messenger wrote that Lucy Griffith became so excited with the outcome that she fainted in the courtroom.

A few years after the trial, Lucy Griffith remarried to Lee Roy Landon and moved to Paducah where she remained for the rest of her life. Lucy Griffith died on March 29, 1949 and was buried in an unmarked grave near her parents in the Strow Cemetery in Benton.