The Birmingham Raid of 1908

Written by Justin D. Lamb

The town of Birmingham is now underwater, inundated by the creation of Kentucky Lake. Underneath these waters lie the secrets of the infamous Birmingham night rider raid of 1908 that caused a mass exodus of African-American residents.

Perhaps no other period in western Kentucky history was filled with more lawlessness and disorder than the year 1908. The era of unrest was attributed to the infamous Black Patch Tobacco Wars which began around 1904 when tobacco farmers throughout western Kentucky formed a protectionist association called the Dark Tobacco District Planters’ Protective Association of Kentucky and Tennessee to oppose the corporate monopoly of the American Tobacco Company (the Duke Trust) owned and operated by James B. Duke.

By controlling the prices of tobacco, the Duke Trust monopoly made it increasingly difficult for tobacco farmers in western Kentucky to make a decent and livable wage. In response, farmers in the Association began to boycott the Duke trust. However, some members of the Association felt that a boycott alone wasn’t enough and what followed was the most violent civil uprising since the Civil War prompting The New York Times to declare, “There now exists in the State of Kentucky a condition of affairs without parallel in the history of the world.”

As tensions began to increase, a faction of the Association became more violent and formed a militant group of “Night Riders” whose purpose was to intimidate and, if necessary, violently punish any farmer known conducting business with the Duke Trust. Violence became rampant in western Kentucky and eventually, the Night Riders would conduct military style raids on the towns of Princeton, Dycusburg, and Hopkinsville where several tobacco warehouses were burned to the ground and many people were whipped. A New York Times reporter who witnessed the raid in Hopkinsville first hand commented, “Whole towns were mob governed; others besieged. Terror reigned, and from one end of the State to another the night riders were busy.” By 1908, Kentucky Governor Augustus E. Willson declared martial law in an effort to restore order to the western part of the state.

Most of the night rider activity was focused east of the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers with very little commotion witnessed in the Jackson Purchase region. That all changed in the spring of 1908, when Dr. Emilius Champion led a group of nearly 200 night riders from Lyon County across the Tennessee River to invade the Marshall County town of Birmingham. Their purpose, however, had nothing to do with tobacco or the ongoing tobacco wars, but was in effort to terrorize and oust the African-American population in Birmingham.

Today, Birmingham lies underwater, an inundated town swept away in the 1940s due to the construction of Kentucky Dam and creation of Kentucky Lake. But at the start of the 20th century, Birmingham was a bustling town that rivaled the county seat of Benton and had a large black population. A stave mill, timber industry, and a tobacco business employed both whites and blacks in Birmingham and an iron foundry across the river in Lyon County also provided employment for both races. The competition for jobs and prime farming land led to resentment of the blacks in the area and steered Dr. Champion to exploit the fears in the community in order to carry out his racist agenda. In early 1908, Dr. Champion formed his own band of night riders to “rid the area of its negro problem.”

To find recruits, Dr. Champion visited the iron foundries Between the Rivers where he laid out his plan to the disgruntled white workers to get rid of the blacks in the area. He soon crossed the river into Birmingham where he began recruiting even more riders including 24-year old Otis Blick who would eventually play a vital role in the night rider saga. According to Buried in Bitter Waters by Elliot Jaspin, Blick was recruited at a public well shortly before the raid when two men stopped him and told him what was to transpire. “They hurried him off to the barbershop where they held an impromptu induction. The men told Blick to kneel and take the oath that he would never reveal the secrets of the organization.”

The first act of terrorism toward the blacks in Birmingham by Champion’s band of night riders came in late January, when two men wearing hoods kicked the door in at the home of Steve and Mary Whitfield. The men were armed with a shotgun and pistol then dragged Steve Whitfield outside where they tied him to a tree and severely whipped him with a horse whip. “We don’t want you living here” was the reason given to Whitfield as the two men rode off. Despite the hoods, Whitfield was able to identify the assailants as Marvin Farley and Tom Chiles, both of whom were his neighbors. In a aggressive act of intimidation, Farley returned to the Whitfield home the following day to purchase a prized hog from Whitfield. “What happen to your door?” Farley inquired as if he didn’t know. Whitfield sold him the hog for a very cheap price and moved out of Birmingham shortly after.

In the weeks following, notices were tacked to telephone poles and fences throughout Birmingham warning the black population to leave or face the consequences. As the winter turned into spring, tensions and anxiety levels were high as speculation began to circulate concerning the fate of the African-American community.

The Birmingham Mill (above) served as a rallying point where the Lyon County riders met with a squad of Marshall County riders before the Birmingham raid on March 8, 1908.

By the first week of March, Dr. Champion was ready to execute his raid on Birmingham. During the late hours of Sunday, March 8, a band of nearly 150 night riders met at a barn in the Brandon’s Chapel community in Lyon County to prepare for their attack on Birmingham. The barn had been strategically chosen as the rallying point due to its close proximity to the road that ran directly to the Birmingham ferry. After crossing the river, the riders were joined by a squad of Marshall County riders who had been waiting by the Birmingham mill.

As Dr. Champion and his riders moved into Birmingham they operated like a well-disciplined military unit. “The men were organized into squads. Each were armed and wore a hood and a single white sash, and the leader of each squad had two sashes crossed on his chest. The squads moved in columns of two; each had a specific assignment. One squad cut all the telephone lines at midnight. Another patrolled the streets to keep residents inside. Other squads were ordered to round up blacks.”

At midnight, gunshots rang out in the streets of Birmingham. What followed was a night of pure hell and mayhem. Shots were fired into the homes of the black residents who were then ordered to come out or be killed. Dr. Champion led a squad to the home of John Scruggs where his entire family of six were beaten and whipped so severely that the lashes cut into the muscles of their legs. Scruggs and his two-year old granddaughter were shot. Around 1am, Dr. Robert Overby was contacted in Benton. He came to Birmingham to help save John Scruggs, but his efforts were unsuccessful as Scruggs and his young granddaughter both died. As Dr. Overby left the Scruggs home, he was threatened by two night riders for helping the Negroes.

A nearby neighbor, Brooks Gaines, heard the gunshots and the screams from the Scruggs home. Fearing for his family’s lives, Gaines grabbed his son and ran to the gully in the field behind his home. “If I get killed, go to Paducah,” Gaines ordered his son. Fortunately the Gaines family was spared. Down the street from the Gaines family lived Lee Baker who took up arms and resisted the riders. “Although he was surrounded by twenty-something night riders, the forty-three year old farmer, firing from inside the house, had already driven off one charge.” Baker managed to wound several Night Riders including Otis Blick when a bullet pierced his hood and lodged in his shoulder. To subdue Baker, the riders gathered kerosene and threatened to burn him out. Out of ammunition, Baker had no choice but to surrendered himself.

Lee Baker along with local black school teacher Nat Frizzell, Alex Terry, Mark Skinner, Annie Bishop, Claude Bishop, and Julia Bishop were rounded up and led to the Tennessee River. The riders also captured one white man, Arthur Griffin as well. Once at the river, those captured were beat and whipped severely. Griffin later told investigators that he was so frightened for his life that he “soiled himself.” Most of the punishment was taken out on Baker who had resisted the riders earlier. “Dr. Champion ordered them to use a ‘good, healthy ox whip’ as Baker was made to bend over a log with his back arched so the whips could cut into him more easily.” Beatings were then given to Bishop and Skinner as the rest were ordered to watch. Griffin was spared from any whipping and given the order to “treat his wife better.”

After the beatings, Dr. Champion found a stump and gave a speech warning his victims, “There are thousands of Night Riders in the United States and their actions would be watched and in the course of time a return visit would be paid.” The blacks were ordered to leave Birmingham and never return. After inflicting his night of terror, Champion and his riders rode off into the night. By sunrise, there was a mass exodus of black leaving Birmingham. They grabbed what they could carry and boarded the steamboats on the Tennessee River. Many went to Paducah. Others fled north to Louisville or to Illinois.

As news of the Birmingham raid reached the Benton courthouse, Commonwealth Attorney John G. Lovett promised justice. A few weeks later, Night Riders threatened Lovett and Circuit Judge William Reed and guaranteed a raid on Benton if a trial was pursued. Notices were posted all across Benton warning the small black population to leave town or face the same consequences as the blacks in Birmingham. Reports of postings were also sighted in Gilbertsville and Calvert City. The Benton Tribune reported “only six negroes remain in Benton since the notices to leave town were posted. It is the general opinion that every colored person in Benton will leave by Saturday night.”

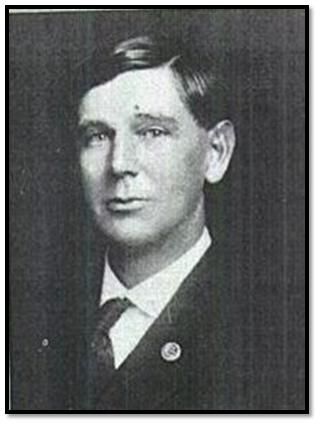

Commonwealth Attorney Lovett issued a public announcement informing the masked riders that their intimidation tactics would not be tolerated and promised that he would proceed with prosecuting the riders to the fullest extent of the law. He also warned the riders if “they planned to attack him then they had better kill him because if they didn’t, he would indeed kill them.”

Commonwealth Attorney John G. Lovett prosecuted Champion and his band of night riders despite threats on his life and property.

Days later, Lovett’s office on Poplar Street (located where Filbeck-Cann & King Chapel is today) was burned to the ground and it was believed that it was an act committed by the night riders. A local “home guard” was formed by the local law-abiding citizens in Marshall County to maintain law and order if a night rider attack were to occur. Eventually, the state militia was deployed to Benton. On April 8, a month after the Birmingham raid, 71 men including Dr. Emilius Champion were identified as the night riders. However, only 11 indictments were handed down. Marshall County Sheriff Pete Eley arrested Dr. Champion and 10 other men who were held on a $2,000 bond in the Marshall County Jail.

As the case came to trial in the summer of 1908, crowds packed into the courthouse to see the drama unfold. The star witness for the prosecution was Otis Blick who made a deal with Commonwealth Attorney Lovett in return for his confession and the identification of the other masked riders responsible for the raid, especially their leader: Dr. Champion. For his protection, Blick was placed in protective custody in Murray with members of the state militia until he was called to the witness stand on June 16.

Blick recounted the events of the night which had led to him being wounded in the shoulder. Blick pointed to Dr.Champion as the chief organizer of the raid and told the court that before the raid that the group was divided into three squads and that everyone was given ten cents a piece by Dr. Champion to buy black cloth to make a mask to be worn during the raid. Blick’s mask which has bullet hole was presented to the court as evidence of his part in the raid. Dr. Robert Overby and Arthur Griffin also testified for the Commonwealth.

In response to Otis Blick’s statement, defense attorney Charles K. Wheeler of Paducah introduced testimony that Otis Blick was incapable of telling the truth and his account of the Birmingham raid should be dismissed. Blick’s father, W.M. Blick, was introduced by the defense where he stated that at age twelve his son had suffered a sun stroke which caused his mind to wander and caused him to be dishonest at times. During cross examination, Commonwealth Attorney Lovett pointed out that Blick had never been examined by a doctor, thus it was not certain if his mind was ever affected by the sun stroke. W.M. Blick also admitted that he had told his son at the courthouse doors just hours prior to his testimony that he would receive $1,000 from Dr. Champion if he would change his testimony and tell the court that he had lied about the raid. The defense disputed claims of a bribe and also called several witnesses from Dr. Champion’s home of Lyon County who all stated that Champion was at home the night of the raid and therefore could not have taken part. Commonwealth Attorney John G. Lovett closed arguments on the afternoon of July 8 and pleaded that the jury do its duty and convict those accused and thus the “fair name of Marshall County might be vindicated.”

After a ten and a half hour deliberation, the jury came back with a guilty verdict for Dr. Emilus Champion for his role planning and executing the raid on the Birmingham. However, the jury dismissed charges for the death of Mr. John Scruggs. Dr. Champion would be sentenced to serve one year hard labor in the Kentucky State Penitentiary in Eddyville. Lovett became the first prosecutor in the Commonwealth of Kentucky to successfully secure a penitentiary sentence for a person guilty of night riding.

With their leader now on his way to the penn, Commonwealth Attorney Lovett set out to bring the other men to justice. The other ten men received lighter punishments or small fines. In October, 19-year old John Prescott of Eddyville was indicted for his connection in the raid. However, before he could be brought to trial, Prescott shot himself in front of his father and sister. The same fate was bestowed onto Ed Fox of Eddyville who was questioned by authorities as to his connection to the Birmingham raid. After disclosing incrementing evidence to the Lyon County Attorney, Fox feared for his life due to betrayal of the night rider code. On Christmas Eve 1908, while walking home with his wife, he shot himself in the stomach.

In a civil trial in Paducah, raid survivors Nat Frizzell and Lee Baker along with the family of John Scruggs were awarded $25,000 each for their suffering. Nearly 60 acres of farmland and 21 city lots owned by the blacks were auctioned at sheriff’s sale at the courthouse in the spring of 1909. All went to whites, some who participated in the raid, for very low prices. Property records show that the city lot Scruggs had bought for $25 in 1902 was sold for nonpayment of taxes. A local white man bought it for $7.25.

As 1908 turned into 1909, tensions began to ease as the night rider activity began to slowly end. Peace had returned to Marshall County, but the county was forever changed by this tragic event.