The Tragedy of Ruben Hamilton and James Culp

On the morning of June 9th, 1864, an order was sent to Reverend Henry Clay Morrison, chaplain of the 8th Kentucky Confederate Regiment, to report to Division Headquarters in Booneville, Mississippi. Upon arrival, Reverend Morrison was greeted by Confederate General Abe Buford who informed him that three young men were nearby in a box-car who had been tried by court martial and were sentenced to be executed at 4p.m.

Two of the boys were 17- year old Reuben M. Hamilton and 16-year old James B. Culp of Marshall County who were serving the 7th Confederate Kentucky Regiment. The third boy was an unknown McLemore boy, also from the same regiment. Reverend Morris had been given the difficult task of conveying the news of the execution to the doomed boys and to provide them with any spiritual comfort in their final hours.

Two of the boys were 17- year old Reuben M. Hamilton and 16-year old James B. Culp of Marshall County who were serving the 7th Confederate Kentucky Regiment. The third boy was an unknown McLemore boy, also from the same regiment. Reverend Morris had been given the difficult task of conveying the news of the execution to the doomed boys and to provide them with any spiritual comfort in their final hours.

As Reverend Morrison began to leave to fulfill his duty, General Buford rose from his seat and said, “Preacher I will accompany you on this sad errand.” Reverend Morrison and General Buford walked together down to the box-car where they found Hamilton and Culp handcuffed together. The McLemore was off to the side handcuffed alone. Once he saw the youth of each of the boys, Reverend Morrison’s heart fell in his stomach as he regretfully informed the prisoners of their fate.

Hamilton and Culp were shocked and overcome with fear.

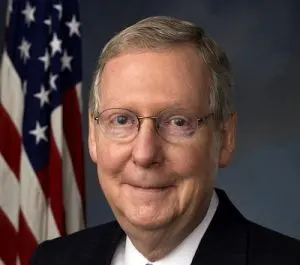

Side: Reverend Henry Clay Morrison

(courtesy of the United Methodist Church, Memphis Conference)

Hamilton turned to General Buford and said, “General, I did not think you would have me shot.” General Buford looked at Hamilton and responded as he took his bandana off and wiped tears from his face, “It was a higher power than I that did it, son.” The order of execution had come from Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest after a court martial had found Hamilton and Culp guilty of desertion. The McLemore boy was arrested, tried, and convicted for “threatening desertion.”

As the morning turned into afternoon, Reverend Morrison spent the day with the boys praying and doing his best to ease their fears by offering spiritual comfort. “I regret to die in this manner.” Hamilton told Reverend Morrison, “I hate for my parents to know I was executed. Though I am not afraid to die. I was converted when I was fourteen years old and I have peace with God and am not afraid to go,” Hamilton continued.

As Reverend Morrison continued to counsel the boys, Hamilton revealed to the preacher the circumstances of how he and Culp came to be in the Confederate Army and why they fled. “I was living at home with my parents in Marshall County, Kentucky and was at church on the Sabbath when a squad of soldiers surrounded the church and took me, with other boys, by force and put us into the army,” Hamilton explained. “I lived in a state which had not seceded from the Union, and therefore I felt I had the right to go back home. I made the effort and was captured, and now I am to die,” Hamilton said. Hamilton then gave Reverend Morrison an unfinished handcrafted ring that he had been making to be sent to his sister back home in Marshall County.

At approximately 4pm on that hot June afternoon, a group of soldiers marched out into the field as the three doomed boys followed in handcuffs. They were led to shallow graves about four feet deep as Reverend Morrison began singing a hymn. The boys knelt as a prayer was given. Before the executions began, the McLemore boy was led away from his grave as his life had been spared but he was ordered to watch the executions of Hamilton and Culp in order to deter him from ever threatening to desert again.

As the soldiers pointed their guns at the two young boys remaining in their own graves, Hamilton calmly looked over at Reverend Morrison and said “Preacher, I shall soon be better than those I leave here. I will soon be happier than those whom I leave.” Culp continued to cry hysterically for mercy as he uttered his last words, “I do not know. Lord help me, I cannot see what is before me.” Reverend Morrison walked to the grave and patted Culp on the head to try to comfort him. He then turned to Hamilton and shook his hand as his eyes welled up with tears. Unable to watch the execution unfold, Reverend Morrison turned and walked away. When he was approximately sixty feet away from the graves, he heard the fatal shots fired. He turned to look back and saw the two lifeless bodies of Hamilton and Culp fall into their coffin-less graves.

Thirty-two years after the execution, Reverend Morrison, who had by that time become a bishop with the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, was on a train that stopped in Booneville Station in Mississippi. As Reverend Morrison stepped off the train, his memory quickly went.

back to that tragic day in 1864. Reverend Morrison asked a man at the station if there was an old field nearby with a grave in it. The man informed him the graves had been moved to the city graveyard but the identities of the bodies were unknown. “Reverend Morrison replied, “I know who they were, and if you will give me a bit of paper I will write their names for you.” The man had no paper, but picked up a new shingle and handed it to Reverend Morrison who wrote the names, “Hamilton and Culp from Marshall County, Kentucky.” The man promised Reverend Morrison that he would place the name on the unmarked graves.

Reverend Morrison remained active in the Methodist Church well up into the 20 th Century. He would often use his personal account of the tragedy of Hamilton and Culp in his sermons and on one account he traveled to Marshall County, Kentucky to visit the relatives of Hamilton and Culp. Morrison published an autobiography in 1917 where he recalled the execution and how it affected him personally: “Hamilton’s death left an impression on me like no other and the impression has remained with me. I can see how a person advanced in years and weary with constant suffering, could grow tired of life and be willing to meet death calmly. But when I saw this youth in the prime of life, afloat with health, with the prospect of a long life before him, calmly face death, it assured me that there is a sustaining power in the simple faith in Christ to be found nowhere else.”