THE LIFE OF JUDGE H.H. LOVETT

PART 10:

CIRCUIT JUDGE

Written by Justin Lamb

By the mid-1950s, H. H. Lovett had been practicing law for nearly a half century and it came as no surprise when his name was on the short list as a candidate for circuit judge of a newly created judicial district in western Kentucky. In the 1953 session of the General Assembly, judicial districts were re-districted throughout the state and Marshall County was placed in the 42nd Judicial District which also included Calloway and Livingston Counties. The appointment for the job was to be given by the governor and Lovett received the endorsement of several county officials in all three counties of the circuit. In April 1954, the Benton Kiwanis, Benton Lion’s Club, and the Marshall County Rotary Club each offered their backing as well.

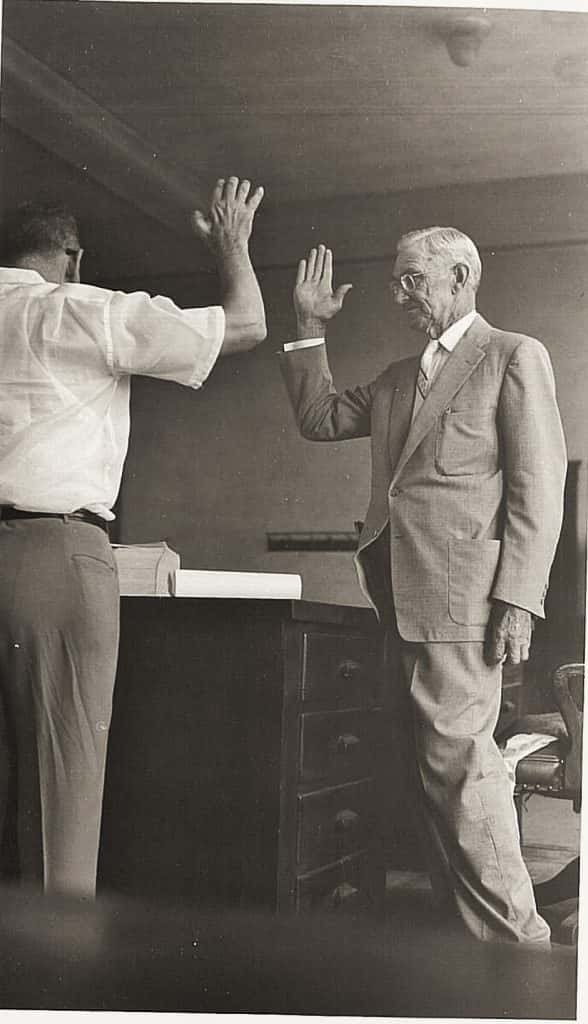

Lovett was officially appointed Circuit Court Judge of the 42nd Judicial District by Governor Lawrence Wetherby on Wednesday, June 23, 1954. On Monday, June 28, Lovett was sworn in by Marshall County Judge Artelle Haltom at the Marshall County Courthouse in the upstairs courtroom. Judge Lovett presided over his first court case on July 5. After his appointment the editorial staff of the “Around the Square” column in the Tribune-Democrat wrote, “Judge H.H. Lovett is due congratulations from Marshall Countians. The county is very proud that a new judicial district is formed and we have the honor of naming the first judge of that district in the person of the honorable H.H. Lovett.” The following year, a special election was called and Lovett won without any opposition.

One of Judge Lovett’s most high profile and most tragic cases as Circuit Judge was the Downing Murder Case. On the night of February 17, 1951, Wanda Mae Downing along with her 13-month old daughter, Nancy Jo Clover, arrived at Dr. George McClain’s clinic in Benton. Downing frantically knocked on the clinic door and was greeted by Doc McClain. Downing told Doc McClain that her daughter was sick and needed help immediately. Immediately, Doc McClain took the child and as he was examining her he discovered that she was covered with bruises on her chest and stomach. Dr. McClain asked Downing what happened to her daughter but received no clear answer. He then advised Downing to rush her young daughter to Murray Hospital immediately.

Taking Dr. McClain’s advice, Downing picked her daughter up and went out to car where her husband Charles Ray Downing was waiting in the driver’s seat. As the couple rode off south on Main Street, Dr. McClain made a call to Sheriff Volney Brien and advised him of the situation. “I think the child has been brutally beaten,” Dr. McClain told Sheriff Brien who promised to look into the matter.

The following morning Sheriff Brien made a trip to Murray Hospital where he discovered that the Downings never arrived. Sheriff Brien returned to Marshall County and went to the Downing home near Tatumsville on Gilbertsville Route 1 where he found that the Downings were gone. Sheriff Brien called on a manhunt to find the Downing family and he questioned the neighbors of the Downing family including Mrs. Dudley Conway who claimed she saw the Downings leave with Charles Ray Downing’s two older children but without 13-month old Nancy Jo Clover. Over the next three years authorities in western Kentucky, along with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, searched for the Downings but to no avail.

By 1954, Sheriff Volney Brien’s term had ended and Billy Watkins was elected and assumed the role as sheriff and continued the manhunt. In November 1954, Sheriff Watkins received word that the Downings were in Fort Wayne, Indiana and he made the trip north to track them down. When Sheriff Watkins arrived, he found Wanda Mae and Charles Ray Downing and the two older children, but there was no sign of the 13-month old baby. Sheriff Watkins questioned the Downings about the whereabouts of the child and Wanda Mae Downing told Sheriff Watkins that the child had died on the night of February 17, 1951 while on their way to Murray Hospital. Sheriff Watkins asked Wanda Mae Downing where the child was buried and why the county coroner was not notified, but received no clear answer. Suspicious of foul play, Sheriff Watkins placed the Downings under arrest and brought them back to Marshall County.

Once back in Marshall County, Sheriff Watkins and Commonwealth Attorney James Lassiter continued to question the Downings as to the whereabouts of the baby’s body. Wanda Mae Downing then told authorities after the child died she and Charles Ray Downing went back to their home and he told her that he paid someone $500 to have the child buried. However, the case took a strange turn when one of the FBI agents investigating the case reported that Wanda Mae Downing claimed during the investigation in 1953 that the child had been sold into adoption. After a week of questioning, Wanda Mae Downing finally admitted to Marshall County officials that her daughter was dead and that she and her husband, Charles Ray Downing, had buried the child in a cemetery in Paducah before fleeing to Fort Wayne, Indiana. Sheriff Watkins took his evidence to the Grand Jury who indicted Wanda Mae Downing and her husband Charles in the disappearance of the young infant.

On Monday, November 15, 1954, Judge Lovett summoned more than one hundred and fifty jurors for the trial of Wanda Mae Downing. The following day, the courtroom was packed with nearly 400 spectators who came to witness the bizarre tale unfold as the trial against Wanda Mae Downing began. The Commonwealth presented evidence that the Downings never arrived at Murray Hospital and Sheriff Watkins also testified that Wanda Mae Downing first claimed to have sold the child, but then admitted that the child had died and was buried in a cemetery in Paducah. Watkins also added that Downing could not remember which cemetery exactly. After an hour and half deliberation, Wanda Mae Downing was found guilty for the disappearance of her daughter. Judge Lovett sentenced her to seven years in Pee Wee Valley Correction Facility.

As the trial of Charles Ray Downing approached, the location of the body of Nancy Jo Clover had still not been found. But in a dramatic turn of events on December 3, 1954, Charles Ray Downing pleaded guilty to the murder of Nancy Jo Clover and disclosed the location of the baby’s body. Sheriff Billy Watkins, Deputy Buck Brien, and Commonwealth Attorney James Lassister along with former sheriff Volney Brien followed the directions given by Downing and found the baby’s body in a steel metal foot locker in the stable of a barn located near the Downing’s old home in Tatumsville. The foot locker had been buried about five feet and a concrete floor had been laid in the floor of the stable. Downing admitted to Sheriff Watkins that he had disciplined the child and got “too rough” and the child eventually died because of the beating. Judge Lovett sentenced Downing to twenty years in the Eddyville State Penitentiary for his crime.

***

As Lovett finished his first full term as Circuit Judge and was preparing for re-election, he became pitted in the middle of a factional divide in the Kentucky Democratic Party. During the early to mid-20th Century, the Kentucky Democratic Party was notorious for being at times a divided party. For years it had been split into two dividing factions, one led by Earl C. Clements and the other by A.B. “Happy” Chandler. The tension between Clements and Chandler began back in the 1935 governor’s race when Clements chose to support outgoing governor Ruby Laffoon’s candidate, Thomas Rhea, in the Democratic Primary instead of backing Chandler. Clements and Chandler had been childhood friends and Chandler viewed Clements non-support as a clear betrayal. After an exciting campaign which included a run-off election, Chandler defeated Rhea in the primary and coasted to victory in the November General Election over Republican candidate King Swope. The Clements-Chandler rivalry quickly intensified which split the party for years to come.

Lovett never officially belonged to any faction of the party, but often supported the candidate he thought was in the best interest of Marshall County and aligned with his conservative views. He was a longtime supporter of Lt. Governor Harry Lee Waterfield who was considered a member of the conservative Chandler faction, but also supported Governor Bert Combs, Senator Alben Barkley, and Governor Lawrence Wetherby who were in the more progressive Clements faction of the party.

Twenty years after his first term as governor, Chandler was seeking the office again and asked the voters of Kentucky to “be like your Pappy and vote for Happy” in the 1955 Democratic Primary. The Clements/Wetherby faction of the party scrambled to find a candidate to oppose Chandler. They first turned to Emerson “Doc” Beauchamp, but later felt his ties to the Logan County political machine would hurt his chances and they quickly abandoned his candidacy. Finally they turned to a political novice, Kentucky Court of Appeals Judge Bert T. Combs of Manchester, Kentucky. Both Chandler and Combs crisscrossed the Commonwealth drumming up support for their candidacies. Out of loyalty to Governor Wetherby for his appointment as Circuit Judge, Lovett threw his support behind Combs early in the race.

In the spring of 1955, Happy Chandler made his way to western Kentucky and stopped in Marshall County to drum up support and visited several county officials to get their endorsement. While in Benton, Chandler called on Judge Lovett at his law office on East 12th Street. The two men had shared a cordial relationship during Chandler’s first term as governor and during his time as U.S. Senator. The exact details of the meeting are not known, but it is certain that two things came out of the meeting. One, Judge Lovett told Chandler that he could not support his candidacy because he had already committed to Comb and secondly, in response, Chandler implied to Lovett that if he won the governor’s race that he would find a candidate to oppose him in his bid for re-election as Circuit Judge and that he would actively work to defeat Lovett for re-election.

Chandler’s threat only made Lovett more passionate about electing Combs and throughout the spring of 1955, Lovett worked tirelessly to elect Combs as Kentucky’s next governor. Combs carried Marshall County and most of the western end of the state, but the experienced and well-known Chandler was the frontrunner all during the race and he waged a notorious negative campaign against Combs. Chandler defeated Combs in the primary by 18,000 votes and trounced his Republican opponent in November. Trouble was coming for Judge Lovett.

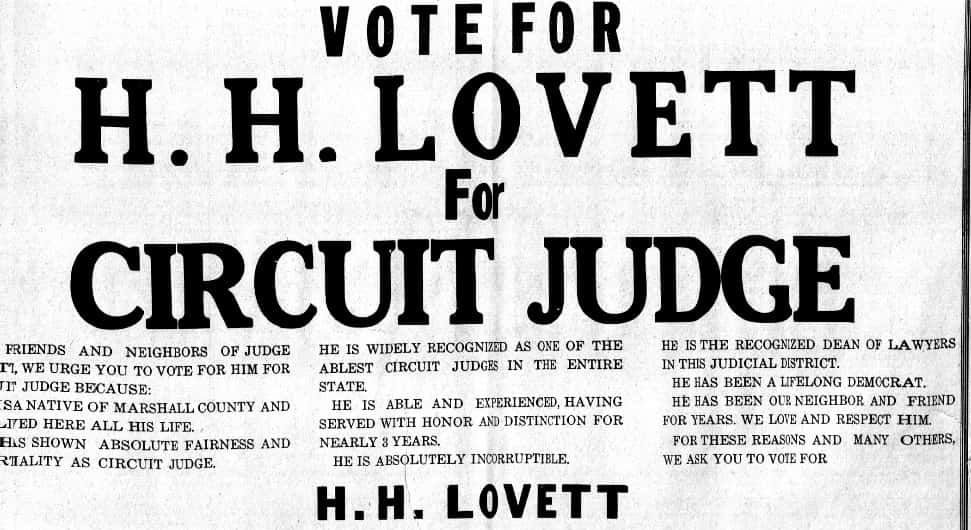

True to his word, Governor Chandler found a candidate to oppose Lovett in the 1957 Democratic Primary for Circuit Judge. That candidate was a young, ambitious attorney, Earl T. Osborne. Born in Paducah and raised in Ballard County, Osborne served in the United States Army during World War II and was at the Battle of Normandy on D-Day. After the war, Osborne went to school on the GI Bill and became an attorney eventually moving to Marshall County where he opened his law practice. Lovett and Osborne were no strangers to one another and even considered one another friends. They both had served on several civic organizations together including the Marshall County Fair Association where Lovett had nominated Osborne as president of the association just a few years prior.

As the campaign drew near, Judge Lovett made his official re-election announcement in the newspapers in all three counties in early April 1957, but he was not prepared for the campaign to come. The race took a negative tone early when Osborne and his supporters began criticizing Lovett for never serving in the military. Osborne supporters pointed to Osborne’s war record in World War II to appeal to the voters who were mostly World War II and Korean War Veterans. Lovett was married with several children during World War I which disqualified him from service during that war and was too old for service in World War II. Osborne spun this to his advantage. The Osborne campaign also attacked Lovett’s age and pointed out that if re-elected, Lovett would be 81 years old at the end of his second term.

As the campaign came to an end and the voters went to the polls on Tuesday, May 27, 1957, Judge Lovett and his family gathered at his home on Walnut Street to listen to the results. As the returns came in over the radio, Lovett listened as he lost precinct after precinct. Surprisingly, Lovett only carried the Olive, Sharpe, Calvert City, Oak Level, West Benton, and Price precincts in Marshall County. Overall, Lovett lost all three counties in the district.

The defeat of Judge Lovett was quite possibly one of the biggest upsets in the political history of Marshall County. However, looking back his defeat was the perfect storm for his opponent and was contributed by many factors.

First, Lovett could not compete with the political machine of Governor A.B. “Happy” Chandler working against him. There were claims that supporters of Governor Chandler used the patronage system with state workers against Lovett. There were accusations by some Lovett supporters that Governor Chandler supporters threatened state workers with the loss of their jobs if they did not vote against Lovett.

Second, campaigning had changed dramatically since Lovett last ran for office in 1934. Osborne utilized the media well and ran a very negative campaign in which Lovett refused to participate. Lovett was used to civility in politics and could not handle the “winner takes all” style of Osborne. Lovett refused to refute Osborne’s attacks and many people began to believe Osborne’s accusations that Lovett was too old to serve and that it was time for a change in Marshall County politics.

Third, Lovett did not do any door-to-door campaigning himself. He left most of the leg work to his supporters. In his official announcement, Lovett cited that his job as Circuit Judge kept him too busy to conduct an extensive door-to-door campaign. Osborne, on the other hand, was seen all throughout the district pressing the flesh and drumming up support. To some of the voters, it looked as if Osborne wanted the job more than Lovett.

Last, and perhaps the most harmful to his re-election bid, was that many of Lovett’s supporters stayed home and did not vote because they believed he was sure to win re-election. Unlike Osborne, Lovett was a lifelong Marshall Countian and had been in the political scene in western Kentucky for years and the voters in Marshall, Calloway, and Livingston Counties didn’t see Osborne as a major threat. They were wrong and underestimated Osborne. With Lovett’s defeat as Circuit Judge, his nearly fifty year career in public service had ended and a chapter of Marshall County politics was forever closed.