Kentucky’s Son:

The Honorable Jefferson Davis

Part II

Written by Justin D. Lamb

The Inauguration of Jefferson Davis as President of the Confederate States of America

(Courtesy of National Archives)

“Judge, whatever Mississippi requires of me, place me accordingly,” Jefferson Davis wrote to Governor John J. Pettus in January 1861 as he learned of the secession of Mississippi. With war on its way, Governor Pettus made Davis a Major General in the Army of the Mississippi. However, one month later, political forces had other plans for Jefferson Davis when the Confederate Congress, which now included the states of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas, met in Montgomery, Alabama to select provisional leaders for the infant nation. Davis was elected Provisional President of the Confederate States of America by acclamation. Davis initially did not want the job of president, but wanted a command position in the military instead. His wife, Varina, later wrote that when he received word that he had been chosen as the new president, “Reading that telegram he looked so grieved that I feared some evil had befallen our family.” Nevertheless, Davis answered the call to serve. After the attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861, the sovereign states of North Carolina, Virginia, Arkansas, and Tennessee joined the Confederacy. The state of Missouri and Kentucky never officially seceded but were given representation in the Confederate Congress due to the strong sentiments felt for the Confederate cause in each state and each given a star on the Confederate flag.

In November 1861, Jefferson Davis was elected as the first permanent President of the Confederacy without any opposition. In the beginning, President Davis was popular among the Southern people and was everything the South wanted in political leader. The Civil War Trust biography described Davis when they wrote, “He had a dignified bearing, a distinguished military record, extensive experience in political affairs, and most importantly—– a dedication to the Confederate Cause.”

But as the war dragged on, Davis’ popularity began to take a hit as political figure experiences during times of tough decisions. Due to the complications and harsh challenges of the newly created position which governed over the infant nation, Davis began to lose favor among the Southern people. His personality and management style didn’t help things either. Davis was described as a “cold and demanding leader” and “impatient with people who disagreed with him. And he had the unfortunate habit of warding prominent posts to leaders who appeared unsuccessful. Davis’ loyalty to these people led to bickering and quarrels throughout his administration.” Davis was also criticized for not properly rallying the Southern people and failed to harbor Southern Nationalism by only giving speeches to small numbers of soldiers and politicians and ignoring the common people. Many historians have asserted that he was a frustrated general caught in the role of a civilian leader.

Davis also suffered from poor health which played a part on his leadership. He was troubled with battle wounds from his days fighting in the Mexican War and suffered from a chronic eye infection that made it impossible for him to endure bright light. He also had trigeminal neuralgia, a painful nerve disorder that causes severe pain in the face which often caused him to seem distant due to his tendency to try to hide his pain.

Davis’ popularity was not helped by the bickering in his cabinet and the growing numbers of Confederate battle defats toward the end of the war. Davis and his Vice President, Alexander Stephens, hardly ever saw eye to eye and Stephens would bash Davis in public at every opportunity. On April 2, 1865, as Union forces began to advance, President Davis was forced to flee the Confederate Capital as Richmond fell to the Yankees. Within hours, President Abraham Lincoln traveled to Richmond and sat behind the desk of Jefferson Davis in a moment of victory.

Around April 12, 1865, Davis who was still on the run, received word of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender to the North. Two days later, on April 14, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth and Davis mourned his fellow Kentuckian’s death and later said that he believed Lincoln would have been less harsh with the South than his successor, Andrew Johnson. In the aftermath of Lincoln’s assassination, President Johnson issued a $100,000 reward for the capture of Jefferson Davis and accused him of helping to plan the assassination. As the Confederate military fell into dismay, the search for Davis by Union officials increased.

According to The Civil War in Louisiana written by John D. Winters, following Lee’s surrender, a public meeting was held in Shreveport, Louisiana, at which many speakers supported continuation of the war. Plans were developed for Davis and the remaining government officials to flee to Cuba where Confederate leaders would regroup. However, on May 5, 1865, President Davis met with his Confederate Cabinet for the last time in Washington, Georgia and officially dissolved the Confederate government. Five days later, Davis was captured in Irwinville, Georgia by Union forces which included among its ranks a young lieutenant, Hazard Perry Baker, who was a native of Trigg County, Kentucky.

Following his capture, Davis was imprisoned for two years at Fortress Monroe off the coast of Virginia after being charged with treason. Irons were riveted to his ankles and he was allowed no visitors and given only one book to read, the Bible. His health began to suffer, and the attending physician warned that Davis’ health was in danger, but this treatment continued until the winter of 1865 when he was finally given better quarters.

During his imprisonment, Pope Pius IX sent Davis a portrait inscribed with the Scripture of Matthew 11:28: Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest. Davis was release on bond in 1867 and was never tried. Davis remained under indictment until he was granted a presidential amnesty on December 25, 1868. Davis’ citizenship was not restored until 1978 when President Jimmy Carter signed the law stating that it “was the last act of reconciliation in the Civil War.”

Jefferson Davis in his later years.

(Courtesy of National Archives, Public Domain)

Following his pardon, Davis traveled the world with his wife before returning to Mississippi. He was once again elected to the United States Senate, but was unable to take office due to provisions in the 14th Amendment which barred ex-Confederates from holding an office in Congress. Davis was then offered the position of President of the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas (now Texas A&M) which he ultimately turned down.

Davis spent the 1880s touring the South promoting his book, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. His reputation began to be restored by ex-Confederates as he received warm receptions all across the region and he attended Lost Cause ceremonies where large crowds showered him with affection and admiration. The Meriden Daily Journal stated that Davis, at a reception held in New Orleans in May 1887, urged southerners to be loyal to the nation. He said, “United you are now, and if the Union is ever to be broken, let the other side break it.”

Jefferson Davis passed away at age 81 on the evening of December 5 at 12:45 a.m. on Friday, December 6, 1889, in the company of several friends and with his hand locked tightly in his wife Varina’s. His funeral was well attended and described as one of the largest in the South. He was first entombed in New Orleans before being moved to Hollywood Cemetery in the old Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia at the request of his family.

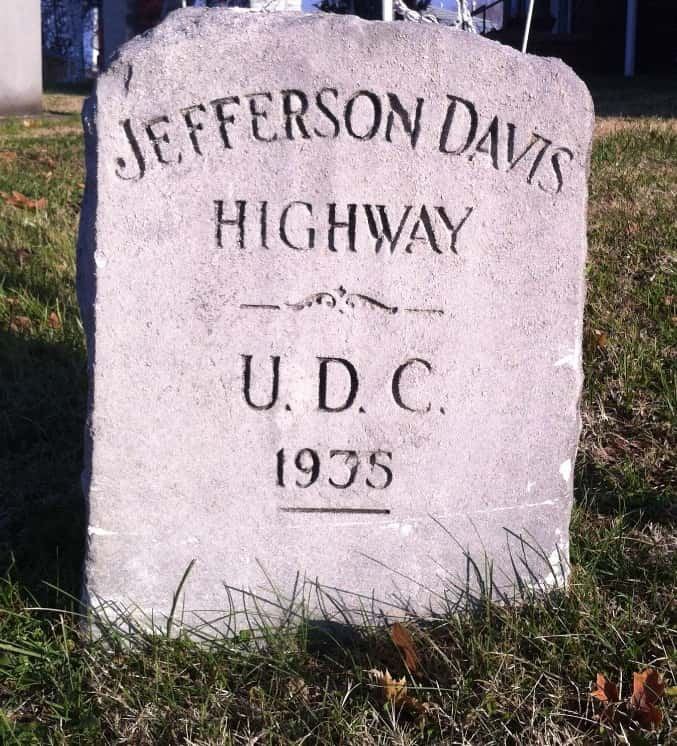

Though he lived in Mississippi the remainder of his life, Jefferson Davis never forgot his birth state (in fact, he named his favorite horse “Kentucky” in fond remembrance) and following his death, Kentucky honored him in several ways. In 1913, lawmakers approved Kentucky’s participation in the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway which was a transcontinental highway to be built throughout the South. In May 1935, a marker dedication ceremony hosted by the United Daughters of the Confederacy was held at the Marshall County Courthouse to officially dedicate a portion of the highway in honor of Jefferson Davis. Speakers included County Judge John Rayburn, County Attorney E.L. Cooper and Commonwealth Attorney H.H. Lovett. The small monument still stands on the southwest corner of the courthouse lawn which officially recognizes Kentucky Highway 408 as the “Jefferson Davis Highway.”

Jefferson Davis Highway Monument on the Courthouse lawn in Benton.

Additionally, the 1922 General Assembly approved a bill, which was co-sponsored by Marshall County State Representative Walter Dycus (whose father-in-law, Turner Harrison Hall, was a Confederate veteran and captured and imprisoned by the Yankees in 1864) to construct the Jefferson Davis Monument at Fairview, Kentucky near Davis’ birthplace in Todd County. The General Assembly also approved the erection of a statue of Davis which is still displayed in the rotunda of the Kentucky State Capital Building along with six other notable Kentuckians.