THE LIFE OF JUDGE H.H. LOVETT

PART 5:

COUNTY JUDGE

Written by Justin Lamb

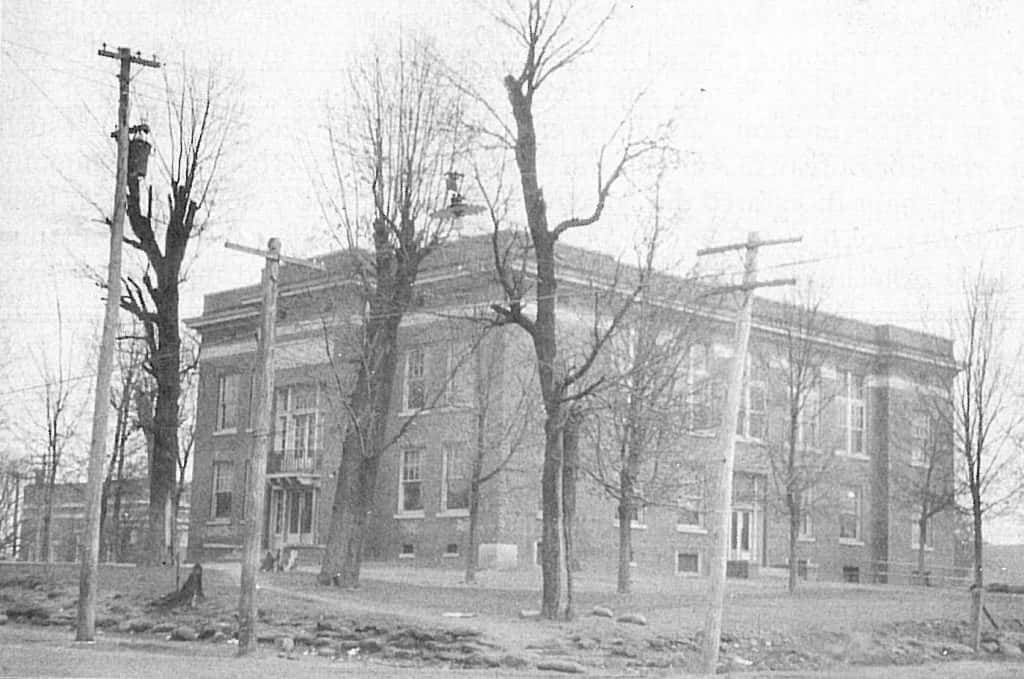

Marshall County Courthouse during Judge Lovett’s term as County Judge in the 1920s.

(Photo courtesy of Greg Travis)

In the beginning of the 1920’s, the country was facing a recession after the end of World War I. Women gained the right to vote and National Prohibition was enacted outlawing the sale of alcohol in the United States. President Woodrow Wilson left office a broken man after a debilitating stroke and Republican Warren G. Harding was elected as his successor after vowing to return the country to “normalcy.” In Western Kentucky, popular Democratic Congressman Alben Barkley of Paducah, a political opponent of President Harding proclaimed “if the Republican administration had returned the country to normalcy, then in God’s name let us have Abnormalcy”. In Frankfort brief talks were in place to build a teacher’s college in Benton, but the plan never came to light as the small town lost out to Murray for the site of the new school which became Murray State Teacher’s College (now Murray State University).

In the early months of 1921, Lovett was at a crossroads in his political life. He had to make a decision of whether to run for re-election as Circuit Clerk which many viewed as dead-end political job or to make the run for County Judge where he could have more of an impact on the direction of the county. While serving as Circuit Clerk, Lovett had witnessed the questionable actions of a few members of the Fiscal Court and he was concerned that the Court was not spending the county’s money wisely. After much discussion with his supporters, Lovett sold his interest in the Tribune-Democrat in February 1921 and announced his intention to seek the office of County Judge of Marshall County. The office of County Judge, which in the 1920s paid $66.67 a month, was responsible for not only the daily business of the county, but also presided over county court which handled in misdemeanor offenses. Lovett saw this as a great way to get a “hands on” experience of law and to make some improvements within the county at the same time. His candidacy garnered a great deal of support throughout the county. With his roots in the southern end of the county and his wife’s family ties in the north end, Lovett was, geographically speaking, a formidable candidate. Naturally, he was backed by many in the Democratic Party who was anxious in restoring a Democrat in the County Judge’s office after the election of Republican Attorney Walter Prince, but Lovett also gained support from many Republicans who believed he would run a clean and conservative administration. At first, Democratic leaders began to recruit a candidate against Lovett because they feared he was too conservative, but eventually those plans were abandoned as no one wanted to take on Lovett and he faced no opposition in either the Democratic Primary or General Election and was elected easily.

As his term began in 1922, Judge Lovett had a momentous task ahead and things didn’t start out too smoothly for him. The county was deeply in debt and the roads throughout the county were in terrible shape. One of his first actions was to propose a measure on the ballot to give the Fiscal Court the power to levy a ten cent tax on every one hundred dollars for the upkeep of county roads. The Fiscal Court was fiercely split on the matter with some magistrates favoring bonds over a tax. Judge Lovett argued that the upkeep of the roads did not pay for themselves and that buying bonds only further kept the county indebted. The measure for the tax was placed on the ballot in late January, but was narrowly defeated.

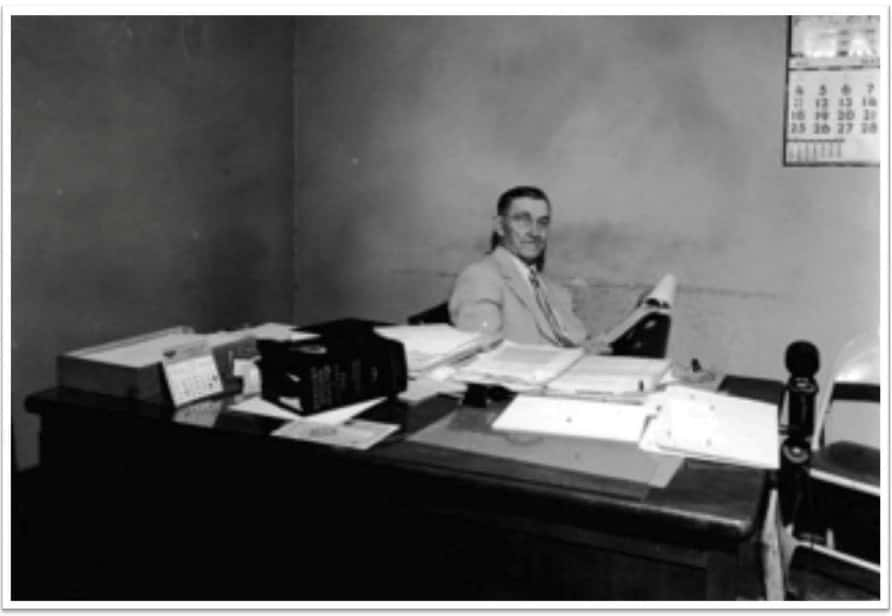

Judge Lovett behind his desk as County Judge.

After the defeat of his road tax initiative, Judge Lovett moved on to his next project of replacing the Goheen Bridge in the Olive bottoms from a wooden structure to a new steel bridge. The project was completed in April of 1922 and was welcomed by those in the Olive community. Later that year, Judge Lovett oversaw the placement of sidewalks around the courthouse and formed a committee to oversee the upkeep of the county courthouse and other county buildings. By 1922, Judge Lovett proposed constructing a new jail in the basement of the courthouse which was completed in 1923. Judge Lovett also created more oversight in county government by appointing a budget commission to oversee and manage the finances of the county.

Judge Lovett led a proactive administration and used his office to promote Marshall County at every opportunity. In years past, the County Judge’s office was occupied by men who mostly focused on the judicial aspect of the job and did very little with the actual business of the county. Judge Lovett saw his term as County Judge as an opportunity to attract more businesses to Marshall County. Judge Lovett and the Fiscal Court worked closely with executives from the Paducah Hosiery Mill to locate a new mill in Benton in 1923. After several talks, the mill opened on Poplar Street and stayed in business until the early 1940s. That same year, Lovett secured the location of the Dark Tobacco Cooperative Society Warehouse on East 12th Street in Benton (where Morgan-Trevathan-Gunn insurance is located today).

Another duty Lovett faced as County Judge was to enforce the newly enacted Prohibition laws in Marshall County. Lovett worked closely with the Marshall County Sheriff’s office by conducting raids on illegal distilleries and chasing bootleggers out of the county. On one occasion, Judge Lovett and Sheriff Joe Darnall conducted a raid on a major bootlegging operation around the Tennessee River and in the process confiscated a Model T Ford that was used to transport illegal liquor. After the raid, the car was taken to courthouse for evidence, and after the trial, it was auctioned off at the courthouse steps. Judge Lovett ended up purchasing the car for fifteen dollars, but he didn’t drive it for months. Finally one day, Sheriff Joe Darnall asked, “Judge, why don’t you ever drive that old T Model you bought.” Lovett replied, “Well, Joe, I can’t seem to get the damn whiskey smell out of the car!” Lovett often referred to that car as his own “Whiskey Dick” which was in reference to a train by the same name that was notoriously known for transporting illegal liquor to Marshall County during Prohibition.

As County Judge, Lovett performed countless marriage ceremonies, and on one particular ceremony, a young couple came to his home late one night looking to get married. Judge Lovett performed the ceremony and after the marriage, the young groom asked Judge Lovett how much he owed him. Lovett replied, “Just pay me what you think she is worth.” The young man reached into his pocket and flipped Judge Lovett a quarter. Needless to say, Judge Lovett got a kick out it and often told that story through the years.

March and April of 1924 saw a public disagreement erupt between Judge Lovett and Marshall County Jailer Ray “Skillet” Darnall. Judge Lovett and the jailer were friends and were elected on the same ticket in 1921, but tensions arose when the jailer began neglecting his duties. In March 1924, it was reported to the Fiscal Court by the Grand Jury that the jail was filthy and the unsanitary conditions were creating serious health hazards for the prisoners. The situation was brought to the attention of the Fiscal Court by Judge Lovett and in a unanimous vote, the court adopted rules for the governance of the jail which mandated the cleanliness of facilities and humane treatment of the prisoners. Judge Lovett also ordered that until the jail was brought back up to standards, the jailer had to answer to the Fiscal Court.

Tensions quickly arose between the jailer and Judge Lovett. Matters became worse when the jailer was arrested in mid-April for public drunkenness in a neighboring county. The following day, the jailer tendered his resignation and in his resignation letter, he acknowledged his neglect and stated that “the people of Marshall County deserve a jailer who will faithfully fulfill his duties.” Judge Lovett appointed W.A. Duese as his successor.

Judge Lovett was a staunch fiscal conservative and this was proven in his years as County Judge. During his term, the Marshall County Fiscal Court experienced a general reduction of all debt and during the last three years of his administration, the county budget even had a small surplus which was a great accomplishment for one of the poorest counties in the state. Judge Lovett is the only County Judge in Marshall County’s history before the construction of the Kentucky Dam to preside over a Fiscal Court that had a budget surplus.

Judge Lovett appointed John A. Henson as County Road Engineer in 1925 and his first task given by Judge Lovett was to take a census of all the culverts and bridges. While Henson conducted his census, Judge Lovett took a census of all the school children in the county. After completing the census of the bridges and culverts a few months later, Henson came to the judge’s office at reported to Judge Lovett that there were close to five hundred bridges and culverts in the county. Judge Lovett revealed to Henson his census of the school children and it was determined that there were more culverts and bridges in Marshall County than there were school children. Judge Lovett was concerned that a few of the Magistrates on the Fiscal Court were passing measures to purchase bridges and culverts because they had an interest in the bridge and culvert company.

At the next Fiscal Court meeting, a representative from the Kentucky Bridge and Culvert Company addressed the court about purchasing sewer pipe, In the late 1970s, John A. Henson recalled this meeting in an interview, “A few of the magistrates were considering buying more sewer pipes and Judge Lovett opposed the measure and made the statement before the court that there were more bridges and culverts in the county than school children. It was about that time that the salesman from the Kentucky Bridge and Culvert Company jumped up and shouted, ‘That’s a damn lie! Why nobody is going to believe that!’ To which Judge Lovett, who had the census reports in his hands replied, ‘I don’t give a damn whether you believe it or not, it’s true!’ The court didn’t purchase any more bridges or sewer pipes during the rest of Judge Lovett’s term.”

By the end of his first term, Judge Lovett left a progressive record as County Judge, but he had made several enemies on the Fiscal Court, particularly Magistrate Homer. H. Rayburn who became a political rival over their differences in the way county government should operate. In 1925 as his term came to a close, Judge Lovett chose not to seek re-election. Lovett had been admitted to the Kentucky Bar and was anxious to get into a courtroom and begin practicing law which had been his lifelong dream. Looking back on his time as county judge, Lovett commented in a 1970 interview with WCBL, “I was never concerned with the politics of the Fiscal Court. My priority was good and open government.”