Press Release from the United States Department of Education Office of Legislation and Congressional Affairs

Press Release from the United States Department of Education Office of Legislation and Congressional Affairs

Marshall County Board of Education has been selected to receive funding under the School Emergency Repsonse to Violence (Project SERV) Program (84.184S). This grant will be in the amount of $138,213.00 for the first budget period (08/03/2018 through 11/30/2018). It is anticipated that the grant will be for a total of 1 year(s).

This program funds short-term and long-term education-related services for local educational agencies (LEAs) and institutions of higher education (IHEs) to help them recover from a violent or traumatic event in which the learning environment has been disrupted.

Description of Impact

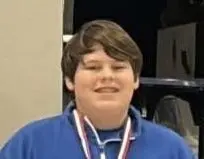

The shooting incident, which occurred in the Commons—the heart of the school, and the area where students and staff gather before, during, and after school hours to socialize—has had an immediate and devastating impact on both students and faculty/staff. Outside of the immediate physical toll (23 total students injured: 16 gunshot victims, and two of those victims now deceased), the psychological and emotional toll on the hundreds of eyewitnesses present, as well as the surrounding community, has been immense.

MCHS houses 1,379 students and 137 staff and faculty, and although concrete figures aren’t available due to the timing of the shooting, it would not be unreasonable to estimate that upwards of 75-85% of these individuals were present in the Commons at the time of the shooting. In addition, several wounded students fled to the neighboring MCSD Central Office, which employs 25 staff. Other students made their way off campus in the initial minutes of the shooting to various nearby businesses and homes, and to the neighboring private K-12 school, Christian Fellowship.

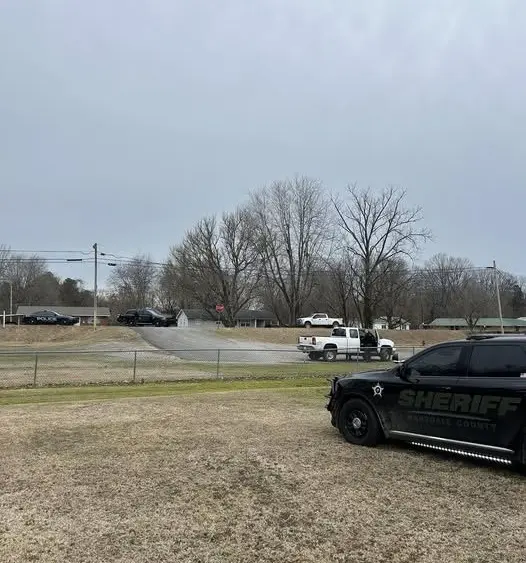

Social media served to compound the panic surrounding the event as parents arrived in droves to the perimeter of the high school campus, looking for their children. When also factoring in the local first responders that handled the scene, the students at NMMS that witnessed the evacuation, the families whose children were impacted by the events, and additional family members and friends within Marshall County’s close-knit communities, the immediate psychological and emotional toll of this shooting has been immense and devastating.

The learning environment has suffered in many ways: students are now afraid to return to school and resume normal activities. Both students and staff struggle to reconcile the concept that the shooter came from within the school community. Parents of students at all age levels are afraid to send their children to school. High school students particularly are struggling with trauma and feelings of bereavement at the sudden loss of their classmates, and informal teacher-student discussions conducted in all classrooms after the return to school have revealed that both students and staff desire additional security features, and that the current armed presence at the school brings them comfort. District staff and funds are being taxed beyond their limits by these additional security personnel (armed guards, bag checks, and security checkpoints upon arrival to school), as well as additional substitutes, overtime associated with the event, and school property that needed immediate cleaning, repair, or replacement.

In addition, emergency counseling and mental health services that arrived in the aftermath of the shooting are now beginning to pull away, leaving a void in our rural community that preexisting local mental health services are not equipped to fill. In the initial week following the shooting, 15 volunteer counselors were seeing upwards of 80-100 students per day at the high school alone, and 4 additional counselors were available for faculty and staff needs.

These numbers do not include the students and staff who almost certainly took advantage of the numerous pop-up clinics (such as the Billy Graham Ministry) stationed throughout the county as an additional resource. Those clinics have long since gone. After the first two weeks, the number of counselors at MCHS reduced from 15 to 10, as the volunteers needed to return to work in their districts of origin. The number of trauma and crisis-response counselors available to students continued to decline after that point, until there were 4 remaining at the start of March.

Meanwhile, local services—including Mountain Comprehensive Care, our contracted mental health partner—lack the infrastructure to see students in crisis at the immediate time of need. Instead, these local facilities are limited to an intake process that includes a professional referral, and counseling may take as long as 3-4 weeks to begin. Students in crisis that are not already established as patients of these facilities must travel hours away, to Bowling Green, KY, for any immediate treatment for minors. MCHS counseling staff have reported that, from their informal observations, threats of selfharm among students have increased dramatically. Where 1-2 students per year may threaten self-harm while in school before the shooting, since the shooting the high school counselors have expressed that they have seen as many as 3-4 of these threats per week, all of which need immediate, individual attention that our current services are ill-equipped to provide.

Students who are unable or unwilling to return to school are also overwhelming the district’s sole homebound instructor, necessitating the emergency hiring of a second instructor. Staff members who were also parents of the injured or deceased students have required long-term substitutes, though the district has done its best to cover those positions with existing staff in order to mitigate the expense. Additional long-term substitutes have been needed for high school staff who could not return in the aftermath of the shooting, whether temporarily or permanently.

We have also seen a dramatic increase in threats of harm from students against the school, both at MCHS and at the two district middle schools. Law enforcement and the school district have taken these threats very seriously, and these ten students have been removed from their respective schools and placed in a separate location in order to be monitored because, given the nature of their threats and the still-raw atmosphere at MCHS, we were uncomfortable housing them with our existing alternative school that is located on the high school campus. We’ve hired additional alternative school instructors to fill that need as well.

We have been advised to anticipate further effects throughout the district and the community in the months following the shooting; namely, a drop in student and staff attendance and an eventual drop in enrollment, an increase in juvenile and adult delinquency, increased substance abuse and domestic violence, and higher demand for mental health supports as individual and community needs become more apparent. Already, between December 2017 data and May 2018 data, total student enrollment in the district has dropped by 80 students, and before the start of the 2018-19 school year we expect that number to increase. In short, the shooting has rocked our close-knit community to its core.

Proposed Activities

Funding for activities in this Immediate Services grant application are primarily encompassed by expenses already incurred for which we request reimbursement. These expenses include, but are not limited to, restoration of the school (cleaning and minor repair); additional security personnel and their associated overtime costs; and substitute personnel, all of which were necessary to return MCHS to a functioning state. Restoring some sense of security was a necessity to convince students and parents that a return to school was possible; this continues to be an ongoing need, as evidenced by feedback from students and staff in the weeks following the shooting event.

The substitutes that we brought onto campus in the immediate aftermath of the shooting were a critical component to returning to a sense of normalcy at MCHS. These subs allowed teachers who may have felt overwhelmed, or who wished to visit an available crisis counselor, to step away from the classroom quietly at any time. They also served as escorts for students who felt uncomfortable walking across the high school campus alone, and served as a comforting adult presence in the halls during class changes. Three of our high school staff found that they were unable to return to work after the shooting, two of those permanently, and long-term substitutes were required to fill those positions as well.

In the days and weeks following the incident, recovery activities included an emotional meeting for all district staff in order to process the event; a walk-through of the high school by MCHS teachers after cleaning and repairs had been completed in order to emotionally and mentally prepare them for a return to school; a soft re-entry day for MCHS students, where attendance was not counted and where emphasis was placed on mental and emotional support after trauma; and various volunteer activities, including a large “deployment” of therapy dogs from a non-profit group, which students particularly enjoyed. Various local and out-of-town mental health agencies also offered their services, and counseling was readily available for students and staff. We intend to continue along similar avenues of mental and emotional support as a complement to ongoing counseling services.

Community building activities have been particularly successful at helping students to heal, likely due to the close-knit nature of our school district and of Marshall County. These activities have included the MCHS Homecoming basketball game and dance (held in an alternate location), various rebate nights at local restaurants, prayer meetings and vigils, and concerts and other performances. The outpouring of support both locally and around the nation has served to buoy up the spirits of MCHS school students and staff. We intend to sustain and encourage these feelings of togetherness and community in order to build up a strong social support network for these victims. The district has since held a public forum on school safety for parents and other community members, as well as additional educational events (such as a presentation on trauma and recovery by Dr. Paul Schonfeld, an expert in child grief, trauma, and bereavement).

Throughout this process, we are making a point to listen carefully to the needs of our students and staff and try to meet those needs as they appear. As an informal survey method, we asked teachers to encourage students to discuss any changes that they would like to see at the school moving forward. From requests to a McDonald’s in the cafeteria to school therapy dog mascots to thoughtful ideas for “paying it forward” through community service days, we’ve made a point to write down these requests and really consider what we have the means and the ability to do. Due to these suggestions, one community service day has already occurred (April 27). All suggestions were added to a Google Doc that could be edited by teachers and viewed by school administration. A recurring request from students and staff has been ensuring safety and security. In the words of one student, “More cops… spread in the whole school” was an item that we knew students and staff needed to feel comfortable, and that we knew we needed to provide. The Marshall County Sheriff’s Department has been extremely cooperative with us regarding this need, and has placed available officers at the high school, provided that we reimburse the expense. We’ve contracted with the Sheriff’s Department to increase the law enforcement presence at our school in these last few weeks, we have paid overtime and extra service for bus and custodial staff to act as monitors in the hallways, and we’ve purchased temporary wandstyle metal detectors to express to these students that we do hear them and we do want to make them feel safe in school again.