“The Saddest Lookin’ Time”

Looking Back at the Spanish Flu Pandemic

Written by Justin D. Lamb

Above: Nine-year old Nellie Lovett (right) and Four-year old Evalyn Lovett (seated in the middle) of the Olive community were victims of the Spanish Flu in the early 20th century. Their sister Winnie (left) and brother Welburn (not pictured) survived the Spanish flu. (Collection of the author)

At approximately 40 million deaths, the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 killed more people worldwide than World War I and has been cited as one of the most devastating pandemics in world history. Known as the “Spanish Flu” or “La Grippe,” the sickness affected 500 million people and wiped out nearly five percent of the world’s population. This deadlier strain of the flu acted differently than previous influenza cases and it seemed to target the young and healthy, being particularly deadly to 20 to 35 year olds as well as the very young and elderly.

Due to inadequate data at the time, the exact origin of the Spanish Flu is unknown with some reports as early as 1916. The flu hit right as World War I was coming to an end and it is believed that the illness may have first appeared at Fort Riley, Kansas and spread with the American soldiers being shipped to the battlefields of Europe. The close quarters and mass movements of the troops were blamed for the increased the spreading of the illness.

The first case of Spanish Flu was officially first reported in the United States in Haskell County, Kansas in January 1918 when Dr. Loring Miner warned the U.S. Public Health Services of a possible incoming pandemic after treating several ill patients. Up until this point, the Public Health Service did not require states to report influenza cases.

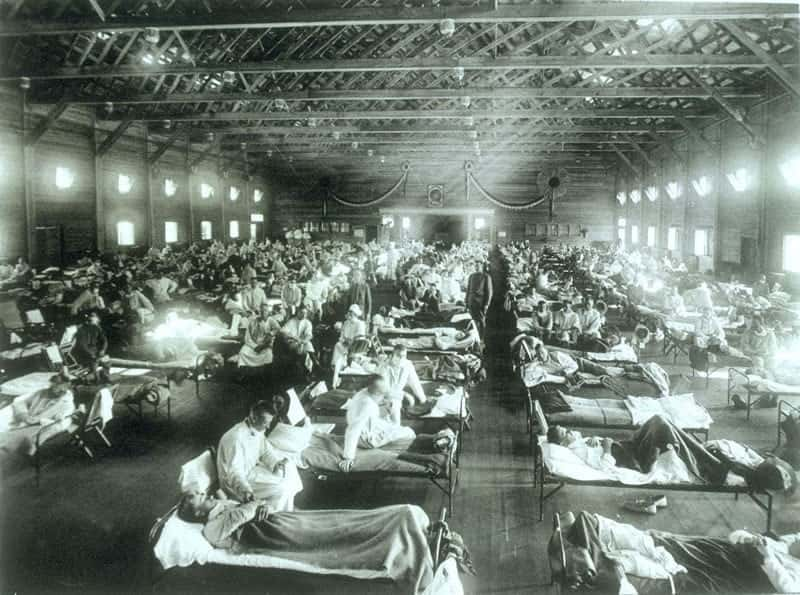

Three months later on March 11, 1918, a company cook Albert Gitchell reported sick at Fort Riley, Kansas. By noon on the same day, over 100 soldiers were in the hospital after contracting the extremely contagious strain of the flu. Within days, 522 men at the camp had reported sick. Later that day, the virus was reported clear across the country in Queens, New York.

Soldiers from Fort Riley, Kansas ill with Spanish influenza at a hospital ward. (License details Public domain (before 1923) & U.S. Gov’t)

To keep the war morale up, wartime censors downplayed the early reports of the illness and mortality rates in the United States, Britain, German, and France were kept secret. However, with Spain’s neutrality in the war, the media was free to report the illness thus creating the false impression that Spain was the origin of the illness. The flu became known throughout the world as the “Spanish Flu” due to the increased coverage of Spain’s 8 million deaths due to the influenza problem. Coverage increased following Spanish King Alfonso XIII’s near fatal bout with the illness in early 1918 only increasing the public’s impression that Spain was where the illness originated.

The Spanish Flu officially first appeared in Kentucky around September 27, 1918 when a group of soldiers traveling from Texas on the Louisville & Nashville railroad stopped in Bowling Green. There the soldiers while visiting the city unknowingly infected several citizens before returning to the train and exiting on.

By the second and third week of the epidemic, Louisville was experiencing about 180 deaths a week from influenza. The situation continued to be bad throughout the fall and into the winter months. Approximately 4,800 deaths were tolled in Paducah. On October 6th, 1918, the Kentucky state health board was forced to issue a state-wide proclamation closing “all places of amusement, schools, churches and other places of assembly.” The public was ordered to wear protective masks while in public.

The exact total or even a rough number of Spanish flu victims in Marshall County is not known due to lack of records. However, one story was recorded from the community of Olive where Oscar and Dollie Lovett lost two of their young children, nine-year old Nellie and four-year old Evalyn, to the Spanish Flu on the same day. As the Lovetts went to bury their two small children in the Horn Cemetery they were prepared for their other two children, eight-year old daughter Winnie and five-year old son Welburn, who had also been infected by the flu, to be dead when they returned. Thankfully, Winnie and Welburn survived. According to oral history passed down through the generations, grave diggers in Marshall County could not keep up with the death tolls as nearly every family in the county was impacted by the Spanish Flu.

In nearby Trigg County, five members of Reverend Jesse Linn Boyd Darnall’s family died in one week as a result of the Spanish Flu. The entire family of eight was inflicted with the flu and the first victim was their 21-year old son Perkins who passed on a Friday. The following day, daughter Elo died and on Sunday, a younger daughter Naomi fell victim. On Wednesday morning, the eldest daughter Martha Dill succumbed to the flu. After witnessing the deaths of four of her children, Mrs. Martha Darnall died as result of the flu a few days later. The family was buried in the Atkins Cemetery.

The Henson family of Trigg County was also hit hard by the pandemic. Seven members of the family died in a two week period. The first to go was Bulah Dee Henson, a 28-year old mother who was expecting a new baby. Eight days later, her husband Will Henson died leaving their two children, Robye and Ruby, orphaned and in the care of their grandparents. Years later their daughter Robye Henson Brown recalled this tragic period, “I don’t remember too much about this time, only that they were very dark and sad times, and that we were hungry sometimes because everyone was too sick to cook or too sad. One of our neighbors would bring food and set it down at the base of a tree for us to pick up.” Jeff Futrell, educator at Marshall County High School and grandson of Ruby Henson Futrell recalls his grandmother’s memories of the death of her parents, “I remember my grandmother talking about this time in her life and how she remembered when neighbors and friends did not come close to the house for fear of catching the flu themselves.” The victims of the Henson family were buried right outside of their home, possibly to efforts to contain the virus.

Further east in Webster County, resident Doy Lee Lovan reported that “the impact of the flu was especially dramatic as it was combined with a smallpox epidemic there. One person from every house on our street died as a result.” In the coal fields of the Eastern Kentucky region of Pike County, a coal miner noted that “It was the saddest lookin’ time then that ever you saw in your life. And, every, nearly every porch, every porch that I’d look at had–would have a casket box a-sittin’ on it. And men a diggin’ graves just as hard as they could and the mines had to shut down there wasn’t a nary a man, there wasn’t a, there wasn’t a mine a’runnin’ a lump of coal or runnin’ no work. Stayed that away for about six weeks.”

With no influenza vaccine at the time, the number of bodies from the fatalities of the Spanish flu quickly outpaced the available resources to deal with them. Mortuaries were forced to stack bodies like cordwood in the corridors of funeral homes. There weren’t enough coffins for all the bodies, nor were there enough people to dig graves. In some instances, mass graves were dug to free the towns and cities of the masses of rotting corpses. The pandemic peaked in the fall of 1918, but influenza remained prevalent throughout the state during the winter and spring of 1919. Even President Woodrow Wilson suffered from the Spanish Flu in early 1919 while negotiating the Treaty of Versallies to end World War I. By 1920, influenza numbers were down to normal.